| ||

| ||

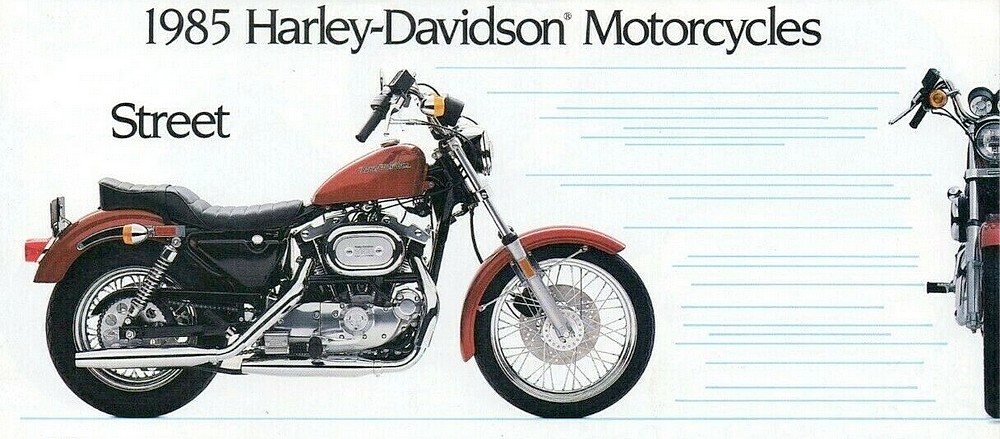

| HARLEY-DAVIDSON XLX1000 (XLX-61) 1984 | ||

| 31-10-24: nieuw avontuur | ||

|

||

| De Honda is weg en dan komt er altijd wel weer wat anders. Ik zit al meer dan vijf maanden zonder Harley en dat is niet goed voor mij. Het budget is beperkt net als de tijd om te zoeken en te gaan kijken. Dus maar wachten tot er vanzelf een betaalbare Sportster voorbij zou komen. Liefst zo origineel mogelijk. Even voor de statistiek, dit is mijn 13e Sportster en mijn 135ste gemotoriseerde tweewieler. Hieronder de eerste foto's. 1984 is nieuw voor mij, die heb ik nooit gehad. Voor zover mij bekend heeft de motor drie eigenaren gehad sinds hij uit Engeland is gekomen. Een Belg, iemand uit Eindhoven en iemand uit Numansdorp. Alle drie geen ervaren sleutelaars zoals je hieronder kunt lezen. | ||

|

||

|

||

| 1-11-24: | ||

|

||

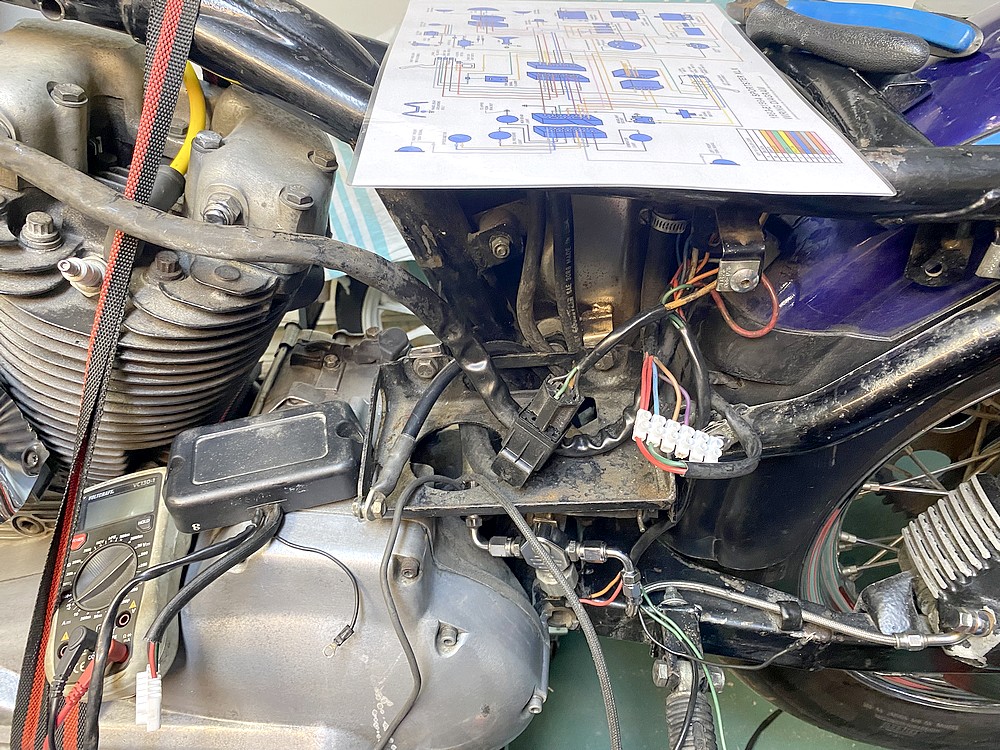

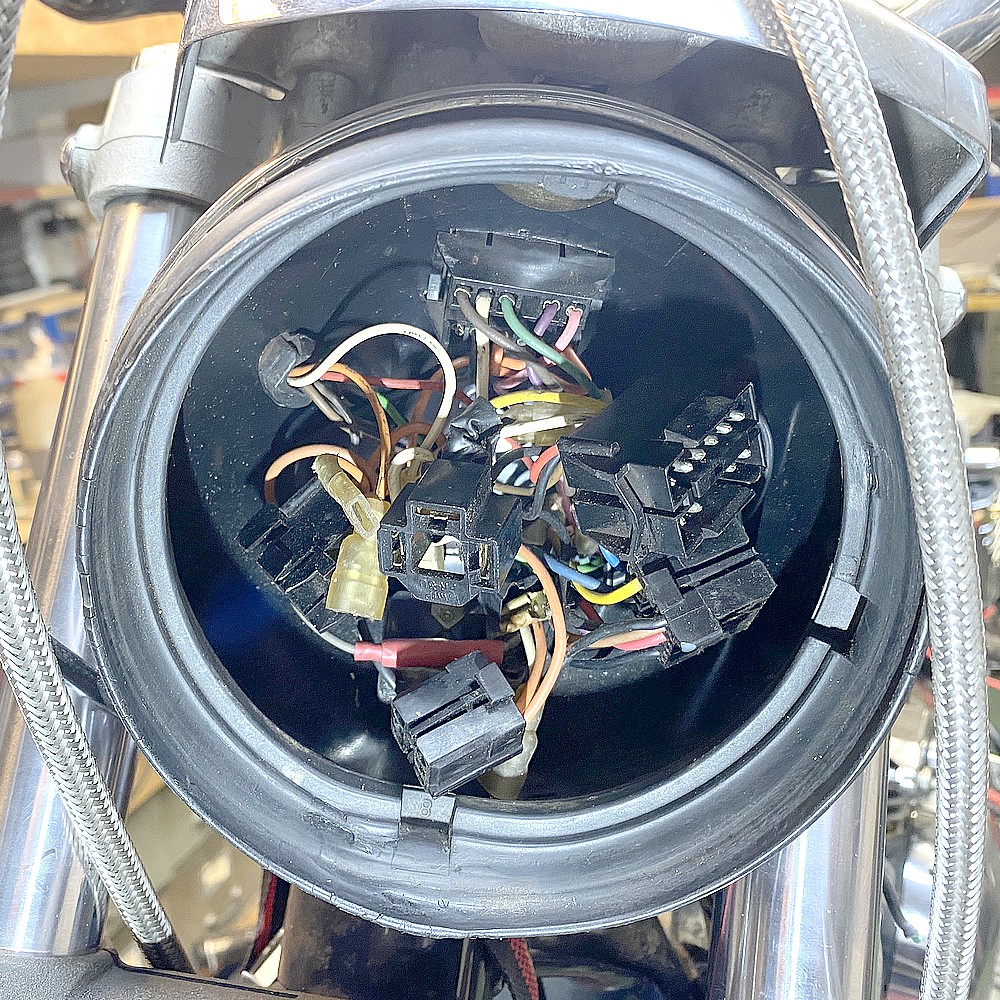

| OK, 1-0 voor de Sportster. Na het verwijderen van de buddy kwam deze draadboom te voorschijn. Daar had hij mij meteen bij mijn zwakke plek. Draadjes is niet mijn sterkste kant. Maar goed, we gaan gewoon door. | ||

|

||

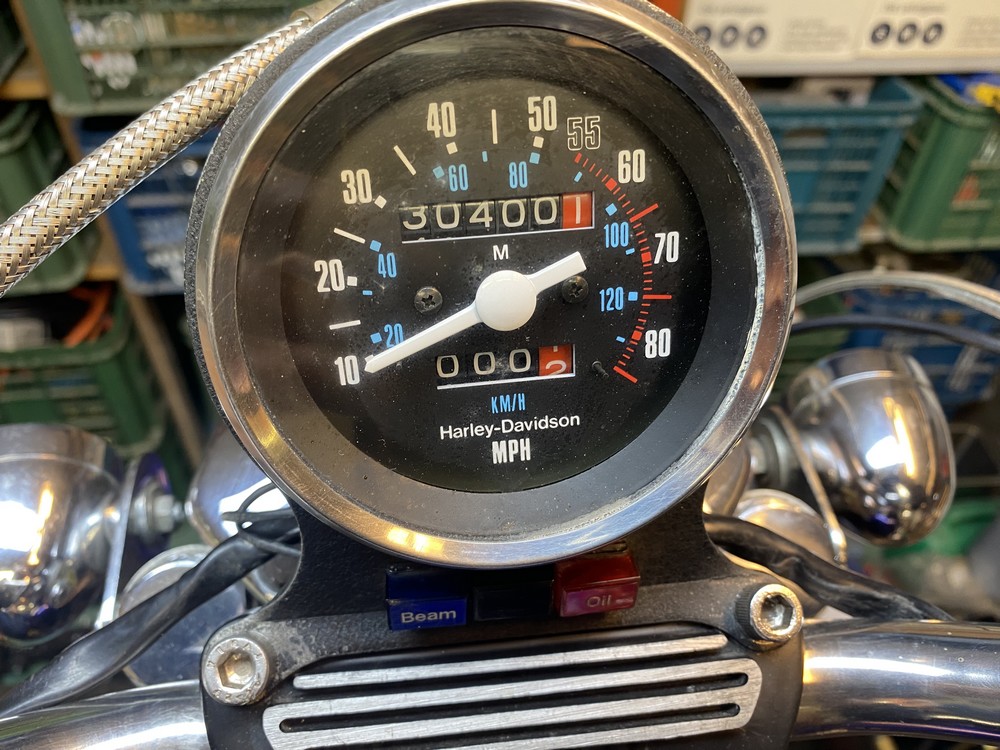

| Kilometerteller is een mijlenteller dus hij heeft ongeveer 45000 gelopen. Niet echt een probleem. | ||

|

|

||

| En dan zit je s'avonds even achter de laptop om te kijken of er info over een '84 er te vinden is. Wat kwam ik tegen? De advertentie waarin de bike werd verkocht in België. Gezet op 24-9-24. Twee maanden voordat ik hem kocht. Ik heb de papieren dus daar staat de naam van de verkoper op, meteen maar een brief naar Kevin gestuurd. Na een paar dagen belde hij mij op en konden we wat info uitwisselen. Zo heeft de motor een nieuwe krukas gekregen eerder dit jaar. Hij is een paar jaar geleden uit Engeland geïmporteerd. | ||

| 4-11-24: | ||

|

||

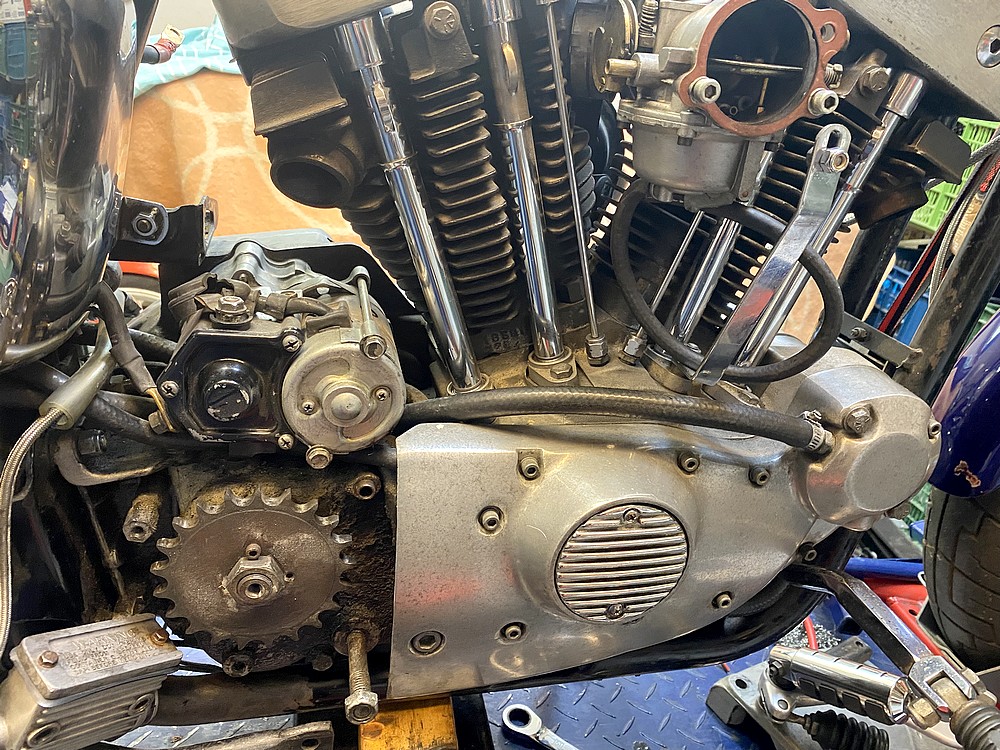

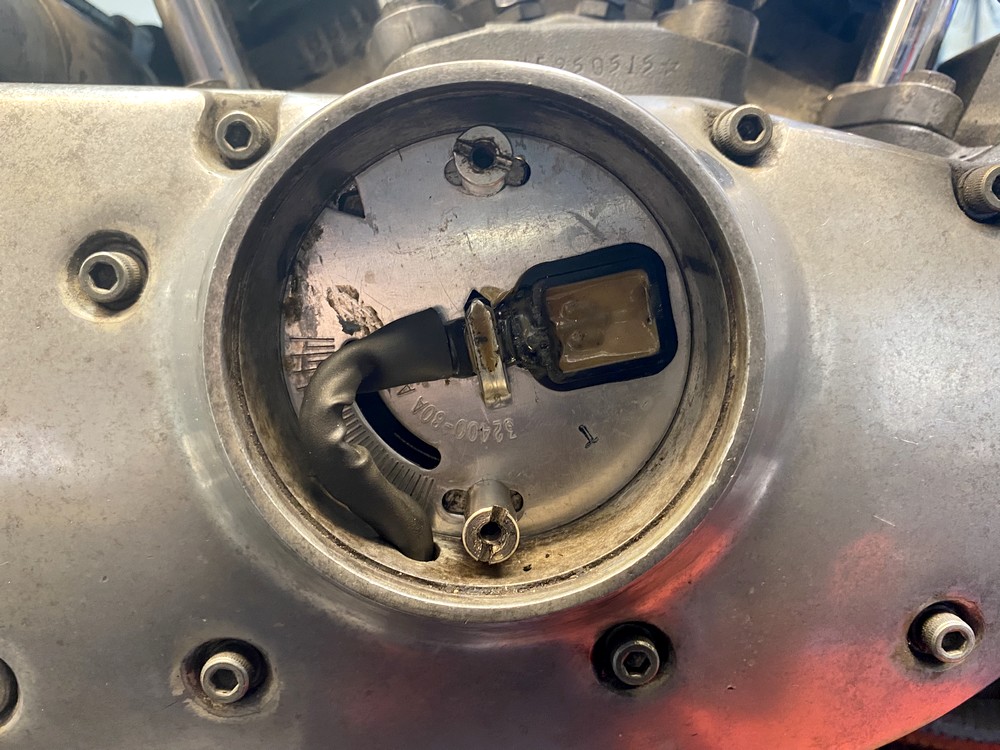

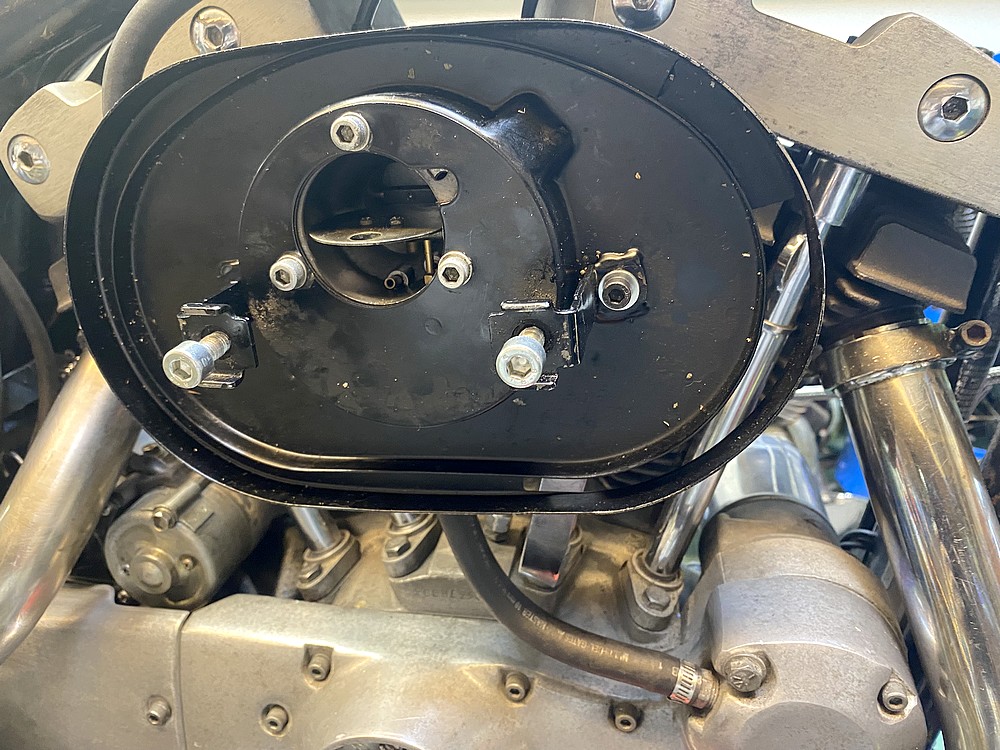

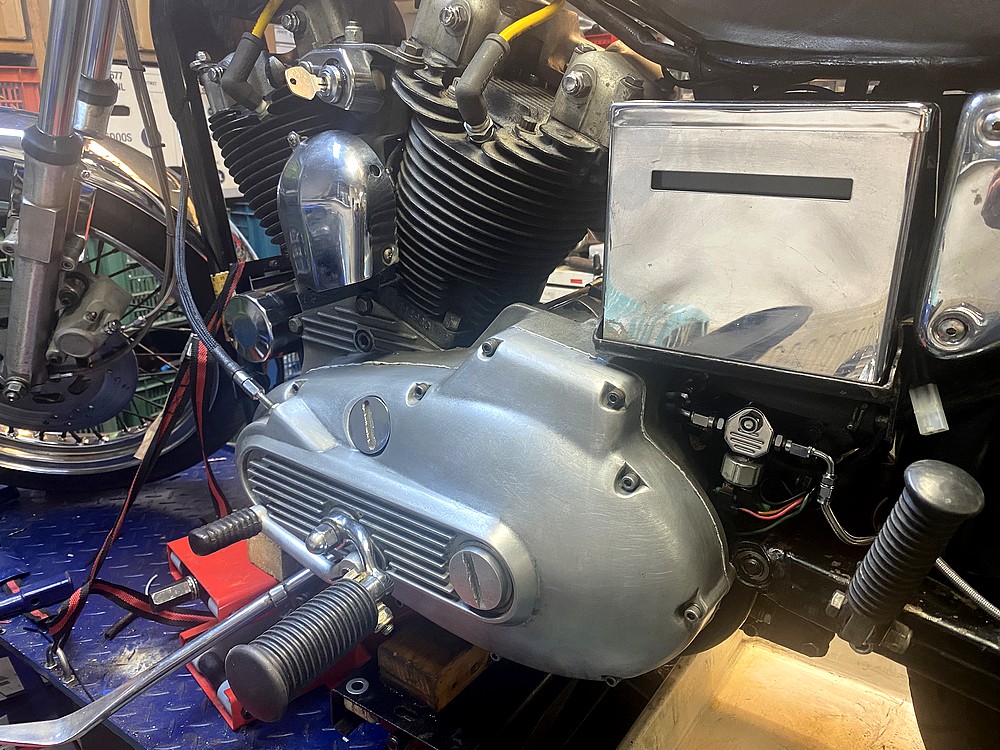

| Ik was niet helemaal zeker dat het blok ook werkelijk "los" is. Er zit geen kickstarter op dus kun je dan aan het achterwiel draaien. Maar er zit geen ketting op dus dat ging niet. Het maakte mij wat wantrouwend. Uiteindelijk maar een kap er af gehaald zodat ik het voortandwiel met een grote sleutel kon ronddraaien. En dat deed hij gelukkig dus ik ga er van uit dat het blok los zit. | ||

|

||

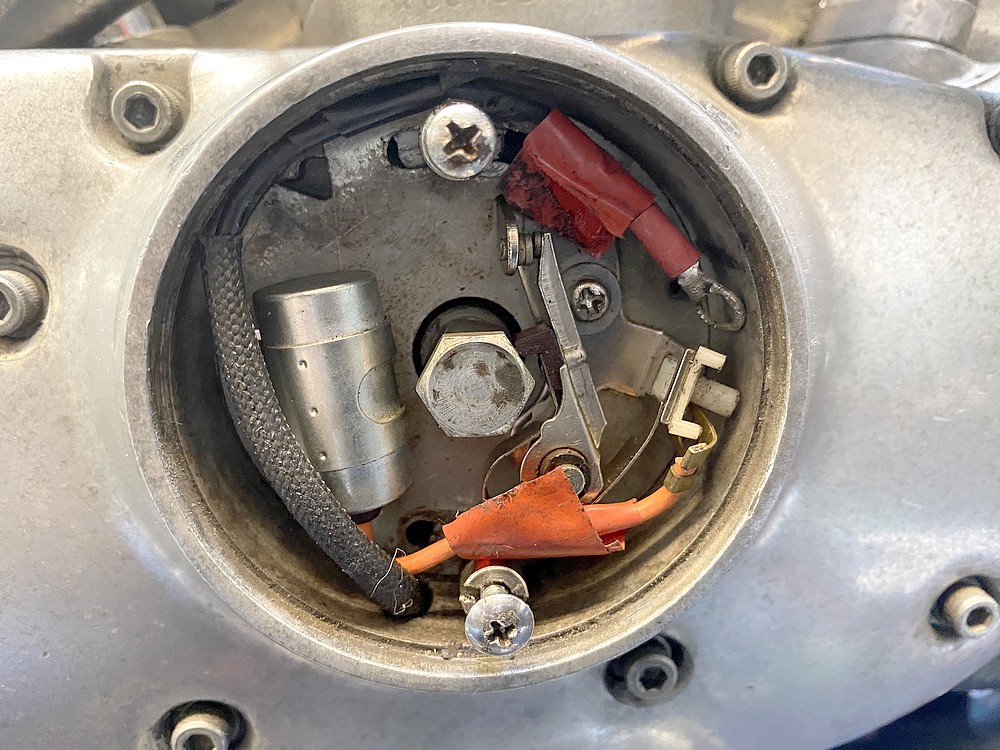

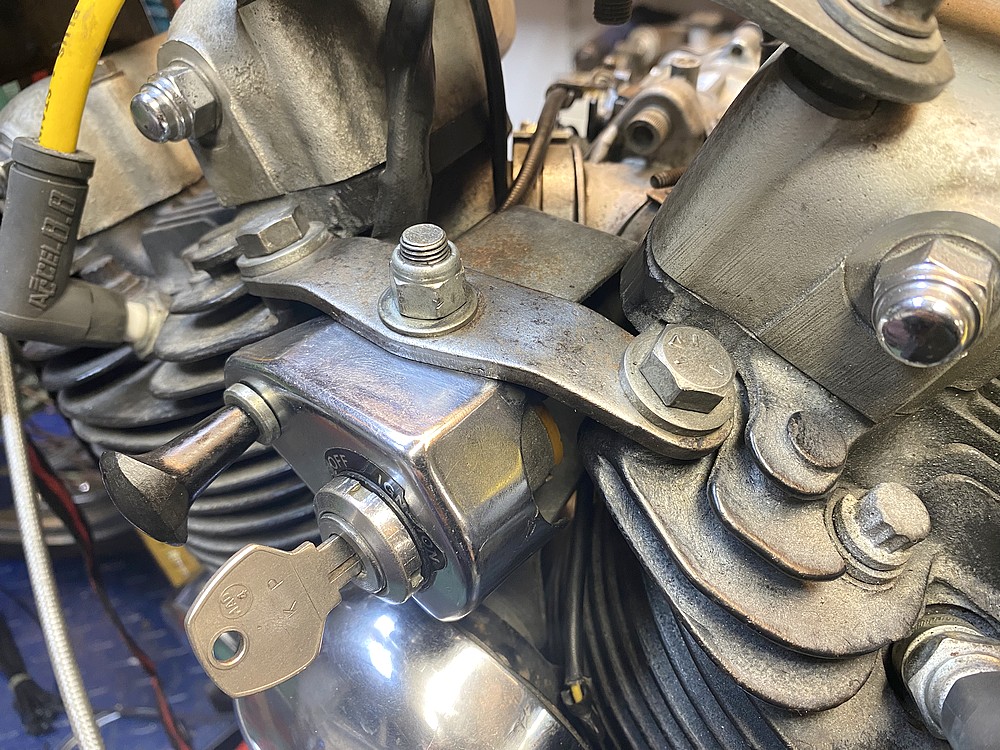

| Gelukkig heeft dit model nog lekker die ouderwetse contactpuntjes. Daar kan ik wat mee. Ziet er allemaal netjes uit voor een 40 jaar oude motorfiets. Alleen zijn de draden niet aangesloten. | ||

| 21-11-24: | ||

|

||

| Eerste poging om de juiste draadjes aan elkaar te zetten. Heb 2 verschillende versies van het bedradingsschema uit 1984 gevonden. Lekker duidelijk. Maar ik volg draadje voor draadje. Ik heb in een tekenprograma een zwart/wit plaatje ingekleurd met de juiste kleuren. Maakt het zoeken wat gemakkelijker. En nee, die kroonsteentjes blijven echt niet zitten maar het is gemakkelijk om het tijdelijk uit te proberen. | ||

|

||

| Restaureren is leren. De ignition controle module ontbrak. Dus op zoek naar een andere. Eerst maar eens bij Feelders langs maar die had niks passend. Dan Ebay Duitsland en daar een module uit 1991 gekocht maar ik twijfelde. Toen maar één in de VS gekocht uit 1980 omdat die in ieder geval met contactpuntjes werkt. We gaan het zien. Nou dat werkte dus niet. Nu gaat het toch weer de electronische ontsteking worden. | ||

| 29-11-24: | ||

|

||

| In mijn pogingen om losliggende draadjes weer ergens aan vast te knopen kwam ik weer van alles tegen. De oliedruk sensor was met een 220 snoertje verbonden waar de helft afgeknipt was. Dus die wilde ik even vernieuwen. Knak zei de sensor dus op zoek naar een nieuwe. Daarna nog uitzoeken waar het draadje dan heen moet. | ||

|

||

| Hier en daar wat gebruikte onderdelen opgescharreld om de contactpuntjes te vervangen voor een electronische opnemer. Is eigenlijk van een ander model Harley maar wel uit hetzelfde jaar. Hopen dus maar dat het ook werkt. | ||

| 1-12-24: | ||

|

||

| En toen was er licht in de duisternis. De lampen van de Sportster doen het en de startmotor draaid zijn rondjes. Er is zelfs een vonk. Feest vanavond hier. | ||

|

||

| Om de juiste draadjes te kunnen volgen heb ik de koplamp er maar eens uitgehaald. Had ik beter niet kunnen doen. Wat een chaos. Hier is duidelijk iemand aan de gang geweest die de moed had opgegeven en de boel maar dichtgedraaid heeft. En ik was de slimme koper. Was alleen maar iets met de bedrading aan de hand werd gezegd. Dat "iets" is wat groter dan gedacht. | ||

|

||

| Overal losgeknipte draadjes. Gelukkig zijn de meeste nog wel terug te leiden waar ze vandaan komen door de kleur maar er zitten nog heel wat losse eindjes. Maar goed, we hebben de hele winter nog. Dat klinkt wat optimistischer dan ik eigenlijk ben. Het zwarte draadje is een losgeknipte aarde draad en de twee grijze gaan naar de richtingaanwijzers. Het middelste lampje zitten helemaal geen draadjes aan maar na bestudering van het schema horen die leeg te zijn. Wordt niet gebruikt blijkbaar. Die hele stekker lag overigens los op de koplamp. | ||

| 5-12-24: | ||

|

||

| Dan ook maar meteen de achterknipperballen er op gezet. Ze branden maar knipperen doen ze nog niet. Komt goed. Dat was snel opgelost door een nieuw relais en hop, knipperen maar. | ||

|

||

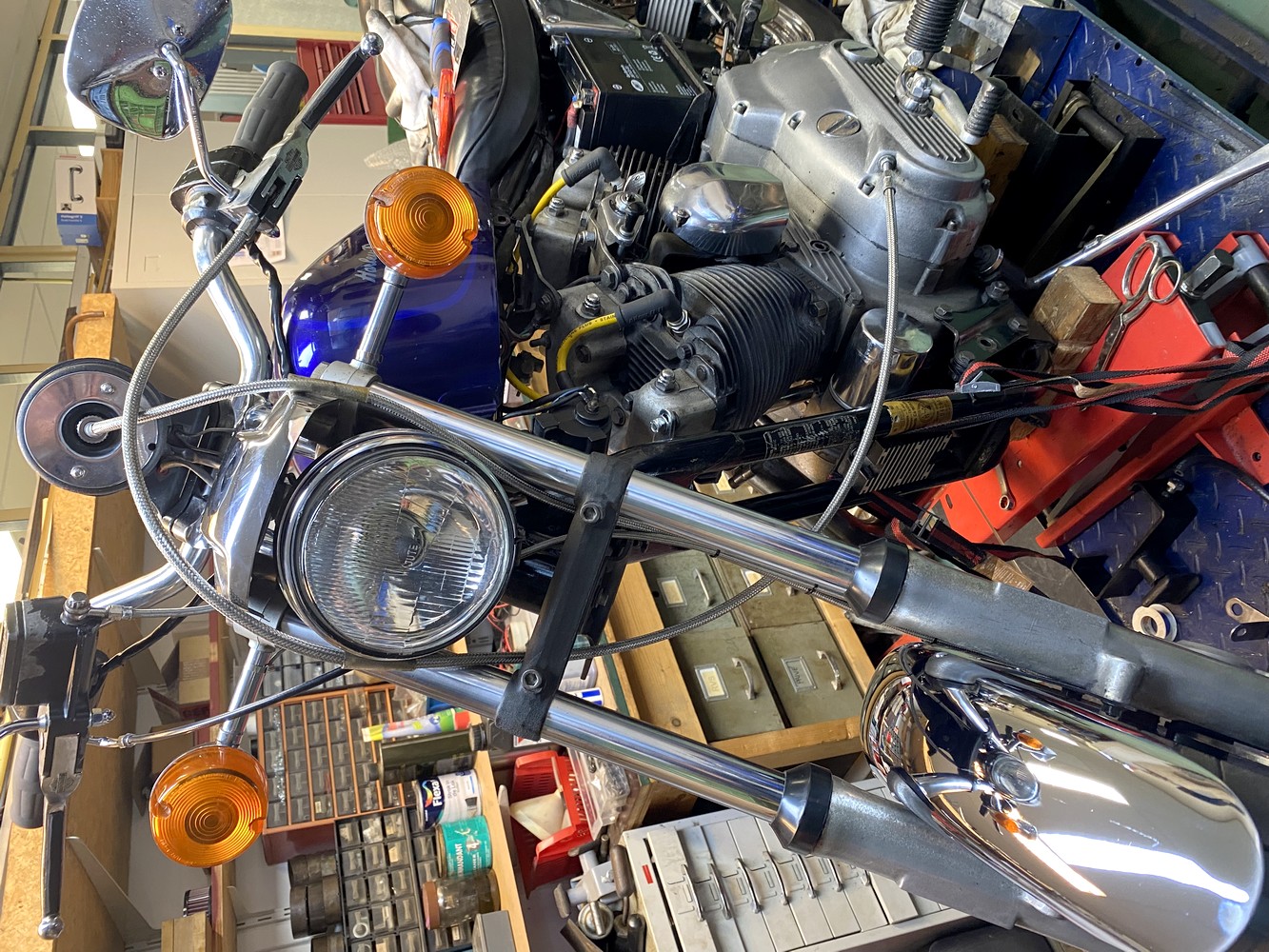

| Niets moet en alles kan. Had vandaag zin om de knippers voor te monteren. Leuk iets opbouwen. Bij mijn vorige Sportsterren vond ik dit model verschrikkelijk en eigenlijk nu nog. Maar gelukkig had ik ze toen bewaard en kan ik ze dus nu weer voor de keuring gebruiken. Win win zal ik maar zeggen. Sorry voor die afschuwelijk lelijke rvs kabels. Komt wat anders voor of ik doe er krimpkous omheen. | ||

| 9-12-24: | ||

|

||

| Vandaag wat kleine klusjes. De hendels zijn van een type dat ik niet ken. Er zit een rubber vulstuk aan de voorkant. Geen idee waarvoor maar waarschijnlijk om de grip te verbeteren. Die vullingen waren weg dus maar twee nieuwe gemaakt van rubber dat nog rondslingerde. | ||

|

||

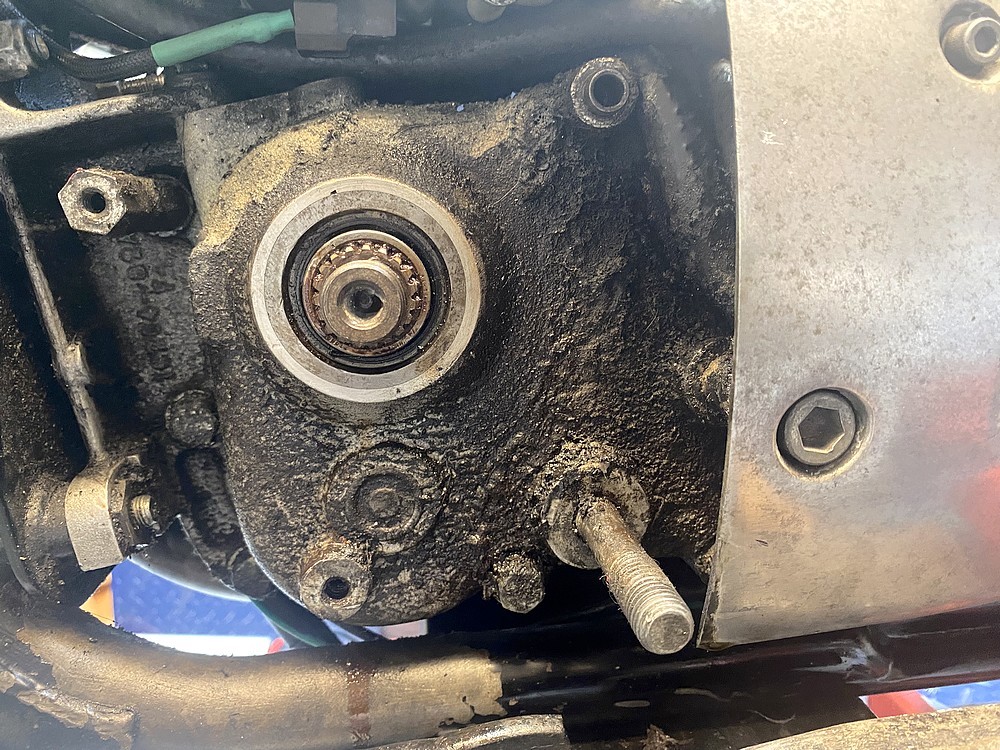

| Het voortandwiel zat niet lekker vast en ik dacht dat dit niet helemaal ok is dus tandwiel er af, lager gecheckt en de boel weer vastgezet maar nu met een borgring. Zit als beton nu. | ||

| 11-12-24: | ||

|

||

| Meestal heb ik wel respect voor de vorige eigenaren of sleutelaars maar bij deze motor wordt dat elke dag wat minder. Vaak zitten er bouten of moeren gewoon los en soms verkeerd gemonteerd. Zo zat de moer die links op de achtervork-as zit verkeerd om waardoor het konische lager niet afgesteld kan worden. Met een hoop gepruts is het gelukt om de moer op de juiste plek te krijgen zodat die niet meer meedraaid en is de speling nu uit die achtervork. | ||

|

||

| Er zat geen chokeknop op de carburateur en een nieuwe vergat ik steeds te bestellen. Gelukkig vond ik nog een door mij afgekeurd exemplaar dat ik niet had weggooid. Kwam van een Electra geloof ik. Met wat pas en meetwerk zit die nu ook op zijn plek. Wel handig als je een choke hebt. | ||

|

||

| In het kader van volstrekt zinloze verbeteringen aan een oude motor, een andere kentekenplaathouder gemonteerd. Vers gescoord van Marktplaats voor 20 euro. Vervangt de wat verroeste originele. | ||

| 13-12-24: | ||

|

||

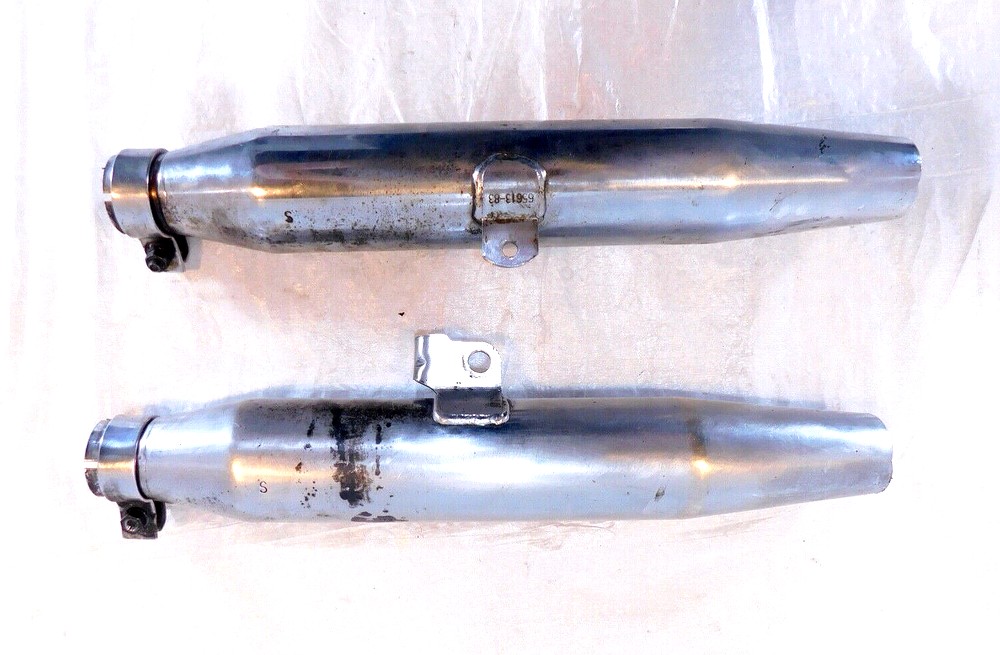

| Vrijdag de 13e, even geen zin om te sleutelen. Morgen een drukke dag in het vooruitzicht dus vanavond maar achter de laptop. Op zoek naar de juiste dempers. Op de voorste demper zit een beugel waarmee je het rempedaal kunt afstellen en die heb ik niet. De uitlaatpijpen zijn inmiddels aangeleverd door vriend Tjolk dus alleen de dempers maar. Partnummers zijn 65605-83A en 65613-83. Conclusie: niet te vinden. Komt goed. | ||

|

||

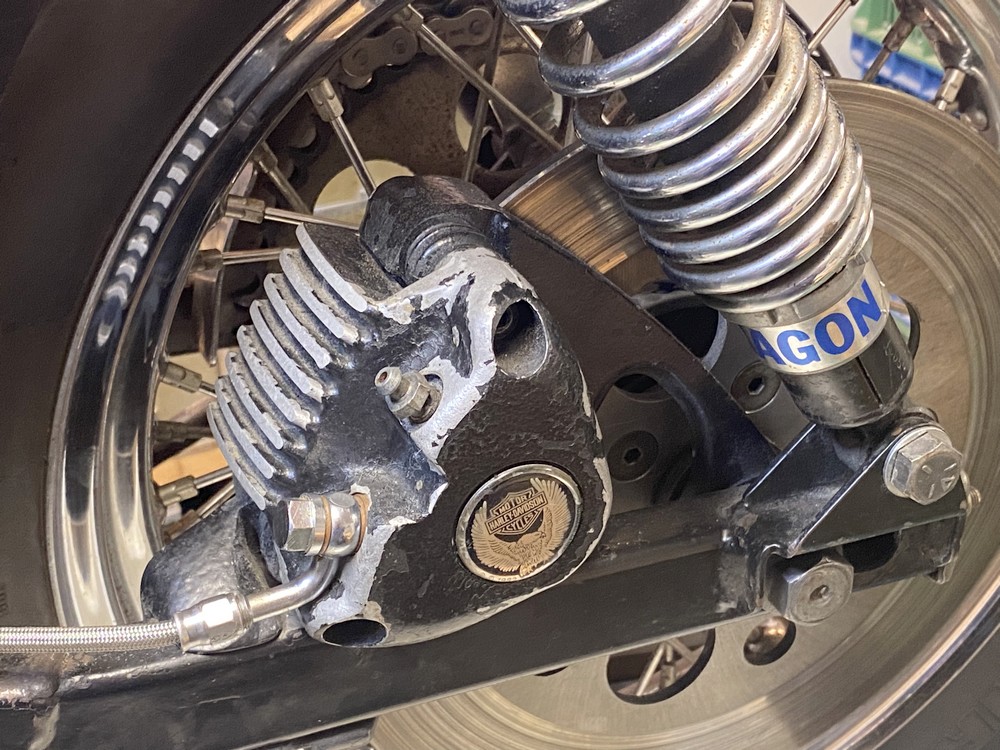

| Ik zit te wachten op de bestelde ketting en de juiste remvloeistof. De Sportster en andere Harleys gebruiken DOT 5 en niet 4 of 5.1. Had dus even tijd om wat op te knappen. Vanavond was de kap aan de beurt waar de rem, reservoir en voetstep op gemonteerd zitten. Na flink wat poetsen, polijsten, nieuw rubber en wat vet ziet het er weer prima uit. | ||

|

||

| Het is misschien wel handig om te vertellen dat ik geen restaurateur ben. Ook geen bouwer hoewel ik er wel een paar van de grond af heb opgebouwd. Ik ga uit van een bestaand model en maak die weer netjes en rijdbaar. Mijn voorkeur gaat uit naar originele modellen omdat ik die vaak het mooist vind. Merk maakt niet zo veel uit maar Harley heeft mijn voorkeur. Voordeel bij Harley is dat originele onderdelen rondslingeren omdat veel rijders hun motoren verbouwen en die onderdelen in de hoek gooien. Daar haal ik ze weer uit. | ||

| 17-12-24: | ||

|

||

| Lief dagboek. Daar gaat het wel op lijken hé. Maar goed, het setje voor de ketting was snel binnen. Is ff klungelen maar ook weer gebeurt. | ||

|

||

| Nou, dan kon de ketting er dus op en afgesteld worden. Meteen maar de zijkap gemonteerd want die lag al klaar maar kwam er achter dat er weer van alles ontbrak uit het reservoir. Moet nog even uitzoeken welke onderdelen maar het zal wel een revisiesetje worden. | ||

|

||

| De verkoper had heel genereus een nieuwe ketting bij de motor gedaan. Bij het passen kwam ik helaas tien schakels tekort. Dus maar een betaalbare ketting van Ebay gescoord. Ben de laatste jaren veel met motoren met cardan aan de slag geweest dus lette helemaal niet op wat ik bestelde. Kwam ik achter toen ik hem "even" wilde monteren. Bleek het een ketting te zijn met een verbindingsschakel die geklonken moest worden. Dat lukt mij niet als hij op de motor zit. Intersnert bood weer de oplossing, er zijn speciale setjes om dat te doen. Daar wacht ik dan maar even op. Zo wordt mijn budgetvriendelijke ketting een dure ketting. | ||

| 18-12-24: | ||

|

||

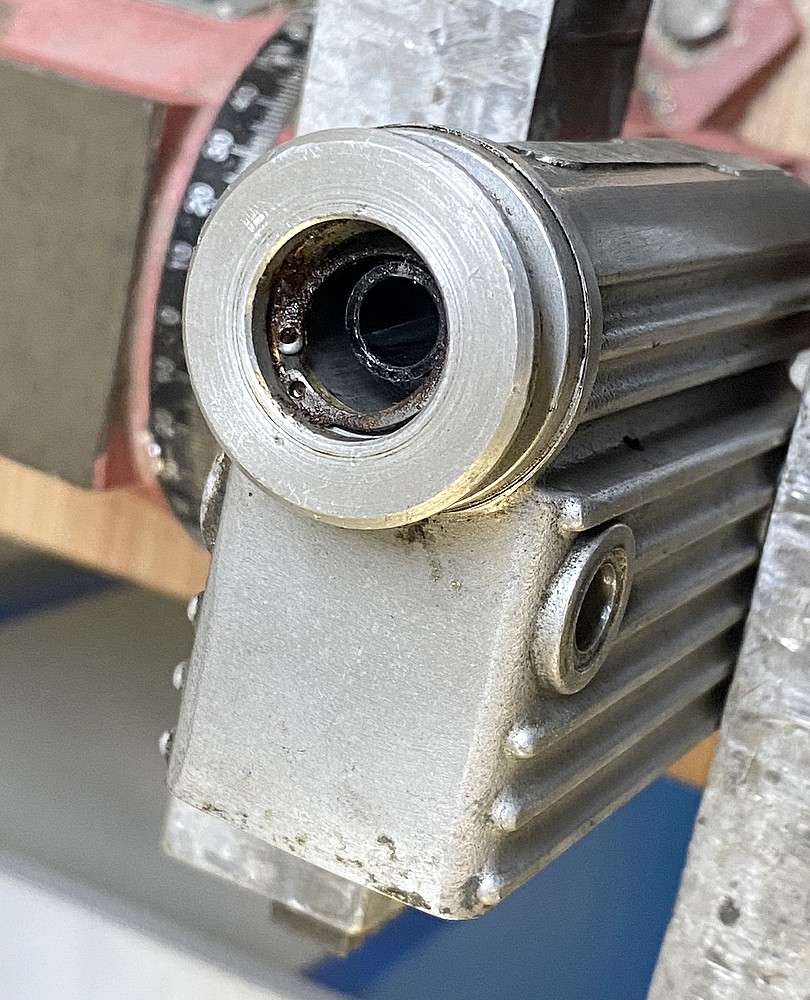

| Ik had het nog een beetje maar nu helemaal geen respect meer voor de vorige sleutelaar. Wie zoiets monteert op een motor verdient geen Harley. Het hele binnenwerk zit muurvast. | ||

|

||

| Maar met wat slimme trukjes is de boel weer uit elkaar en ligt nu in de ultrasoon. Misschien toch maar even een revisiesetje bestellen en monteren, het is tenslotte de achterrem. | ||

| 20-12-24: | ||

|

||

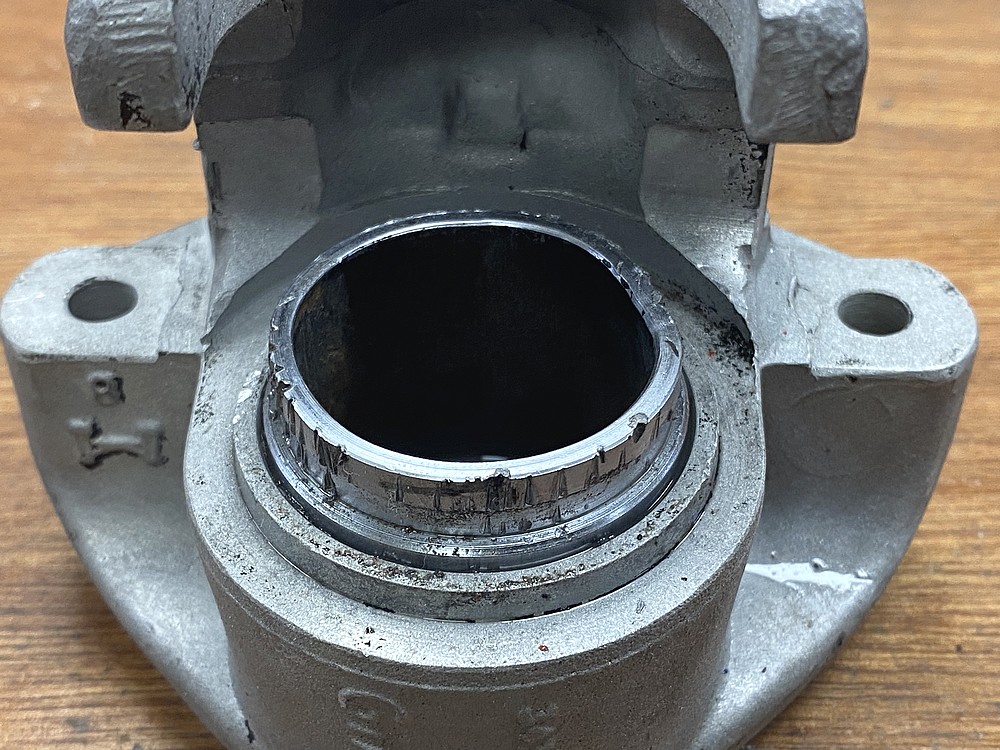

| De dag waar geen rem op zit. Of eigenlijk, de motor waar geen rem op zit. Schreef ik gisteren nog dat ik weinig respect had voor een vorige eigenaar, dat respect is nu omgeslagen in teleurstelling. Wat een knoeier moet dat zijn. Ik zat weer op onderdelen te wachten van de rempomp dus dacht even de remklauw mooi te zandstralen omdat ik dat matte aluminium nu eenmaal mooi vind. Bij het demonteren bleken er helemaal geen remblokken in te zitten. Geen. | ||

|

||

| Ook een keuze kun je denken. Maar dan hecht je weinig belang aan je leven. Hoe kun je een motor verkopen waar geen remblokken in zitten? Ik heb echt geen idee. Maar goed die zijn te koop dus het hele ding maar mooi gestraald. Nog even de zuiger er uit halen maar die was toch wel wat beschadigd. Iemand had het al eens geprobeerd zo te zien. Ding zat muurvast en geen beweging in te krijgen. Ook met een compressor niet. Afschrijven dus maar en op zoek naar een andere. | ||

|

||

| Kijk maar even naar de beschadigingen rondom. Een paar zijn er van mij omdat ik nog probeerde om hem er uit te halen. Ik gaf het maar op. Vast is vast hoor je wel eens, klopt. | ||

|

||

| Een hele nacht in de kruipolie en met behulp van een verfstripper lukte het uiteindelijk toch en met veel geweld natuurlijk. Zuigertje is overleden maar de remklauw is nog prima bruikbaar en rond. Ook weer opgelost. | ||

|

||

| Voor de zekerheid ook de voorste remklauw verwijderd en die ziet er iets beter uit. Er zitten in ieder geval remblokken in. Maar niet goed genoeg om weer te monteren. Dus maar weer op zoek naar onderdelen. | ||

| 22-12-24: | ||

|

||

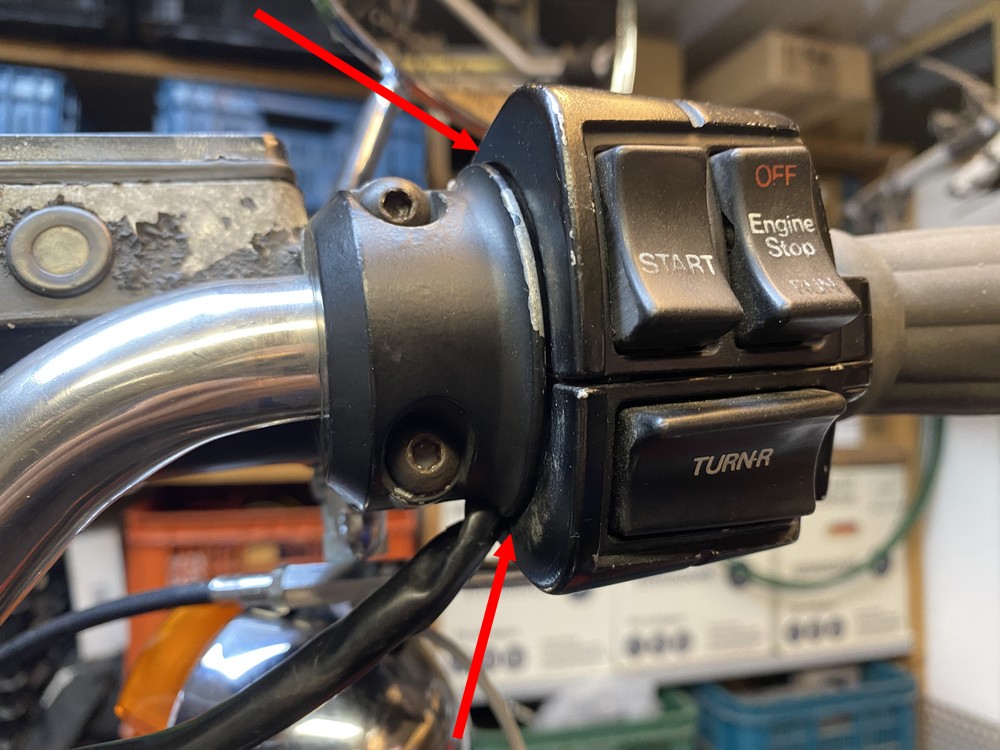

| Soms zijn er van die kleine dingen waar niet 1 2 3 een oplossing voor is. Zo bleef het remlicht maar branden. Achter zit er een schakelaar op de remleiding maar die was afgekoppeld. Voor kon ik geen schakelaartje (meer) vinden. Ik vond een site na een tip van Feelders waarop alle onderdelen staan met nummer er bij. Handig en hij heet Ronnies.com. Na bestudering van de plaatjes van de stuurhendels en knoppen zag ik toevallig waar de oplossing zat. Herinnerde mij toen pas dat ik dat in het verleden al meerdere keren had opgelost. De remhendel en de schakelaar zitten apart op het stuur gemonteerd. Als daar ruimte tussen zit dan kan de hendel het schakelaartje niet voldoende indrukken. Beiden even beter gemonteerd en opgelost. | ||

|

||

| Op de originele dempers zit een beugel met daarop een stelbout voor het rempedaal. Die dempers heb ik niet, nog niet. Daarom uit een rondslingerend hoekijzer maar een beugel gemaakt die op de bevestigingsmoer kan schuiven om de juiste afstelling te maken. Als het niet werkt kan ik er altijd nog een stelbout op monteren. Maar werkt zo prima. | ||

| 24-12-24: | ||

|

||

| Met de feestdagen in het vooruitzicht wordt het wat rustig met het scoren van onderdelen. Ik zit te wachten op spul voor beide remmen. Inmiddels de voorrem ook maar even een straal behandeling gegeven. Als je het niet wilt valt de verf er vaak vanzelf vanaf. Daar staat tegenover dat als je de verf er af wilt hebben er vaak drastische maatregelen nodig zijn. Met andere woorden, ik kreeg de verf er niet af. Een vers blik afbijt gaf ook niet het gewenste resultaat. Dus met staalborstels, schuurpapier, schrapers en tenslotte wat afbijt kon ik het ding nog stralen. Ook weer gebeurt en de rest moet nog schoon. | ||

|

||

| 27-12-24: | ||

|

|

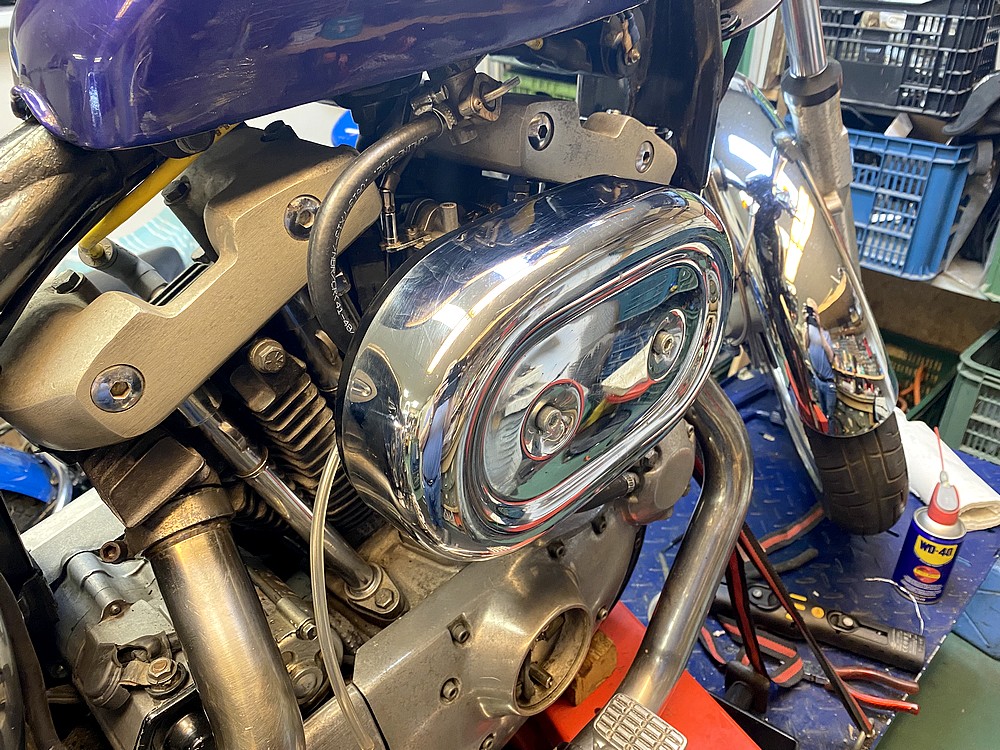

||

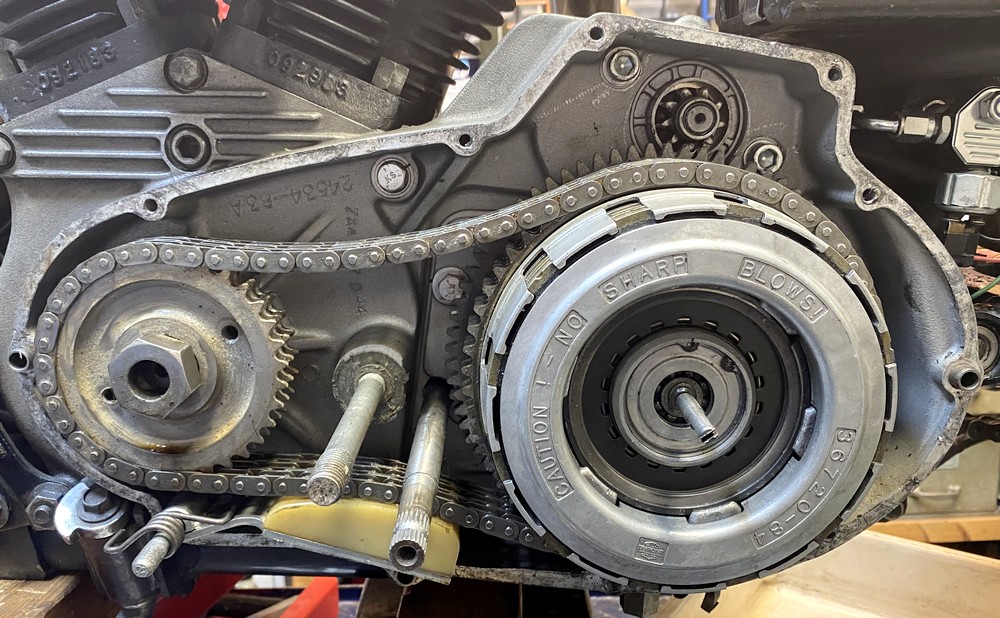

| Vond nog een foto van de bike in de Engelse uitvoering. Kijk maar naar het belastingplaatje op de rechter vorkpoot. Soms lees je van die dingen die jouw motor net weer wat "anders" maken dan al die andere. Neem bijvoorbeeld de koppeling. Die is nieuw voor het 1984 model. Nu uitgevoerd met een aluminium koppelingshuis en koppelingsplaten. In plaats van zes klassieke veren zit er nu één diafragma veer in. Die verandering maakt een flink verschil. Je hebt veel minder kracht nodig om de koppelinghendel in te knijpen. Van 8 naar 2,7 kg. Er stroomt meer olie door de nieuwe smallere koppeling en dat helpt om warmte af te voeren. Omdat hij smaller is kon er een 240-watt dynamo achter de koppeling gemonteerd worden. Die dynamo vervangt de 156-watt dynamo die aan de voorkant van de carter was gemonteerd. Daar zit nu een oliefilter. Het resultaat is dat de motor uit 1984 lichter is dan die uit 1983, meer elektrisch vermogen levert, een lichtere koppeling heeft en mechanisch wat stiller is geworden. Hij is in die uitvoering maar twee jaar gemaakt. 1986 kwam de EVO. | ||

| 4-1-25: | ||

|

||

| Het nieuwe jaar begint al goed. Soms zit het mee en vaak zit het tegen. Ik heb het dan over de prijs van onderdelen. Het meeste vind ik wel op Marktplaats, Ebay of Feelders maar vaak ook bij bekenden. 16214-81 kon ik nergens vinden en in de younaaitzesteeds was een gebruikte $35,- en daar kwam dan hetzelfde bedrag aan verzendkosten bij. Maar na een paar dagen goed zoeken bleek er nog één bij de locale Harley dealer te liggen. Snel daar naar toe en precies 7,09 euro afgerekend. | ||

|

||

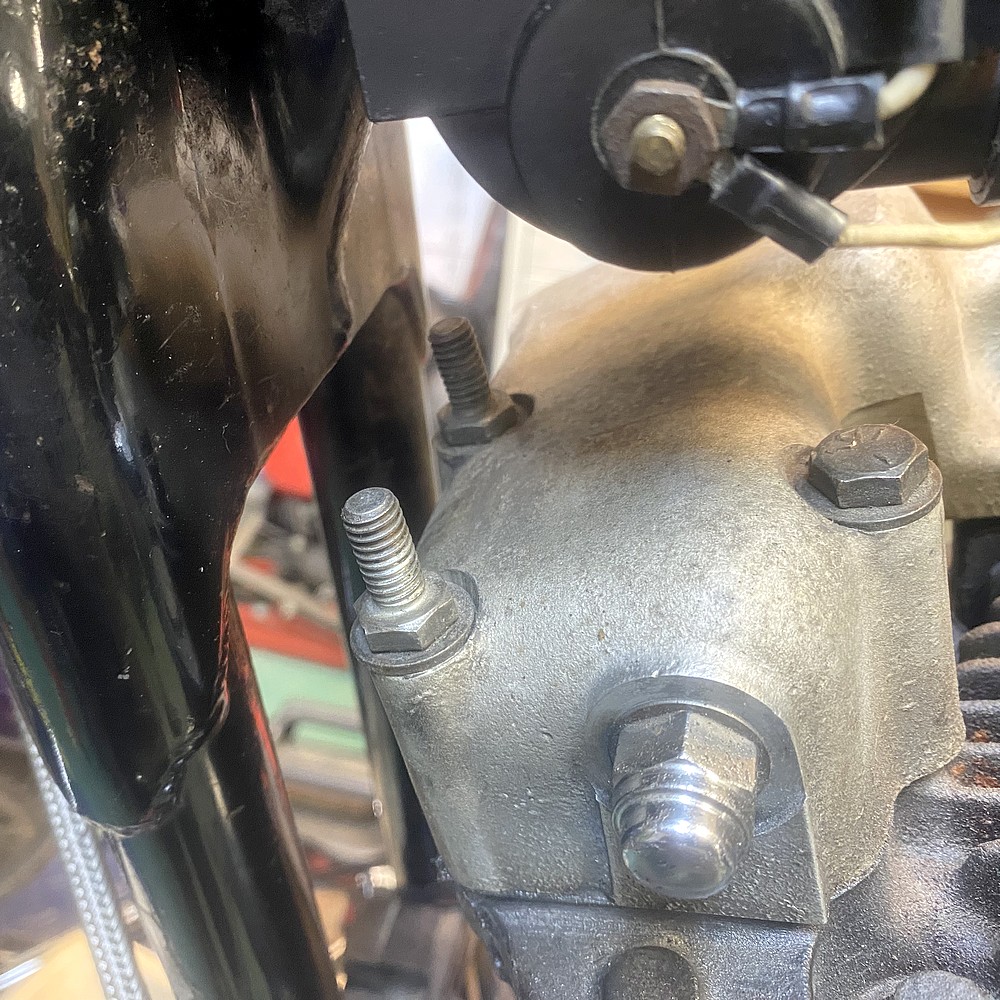

| Nou heb ik al en aantal Ironheads gehad maar soms kom je wat tegen dat ik gewoon vergeten ben. Op de voorste cilinderkop (tuimelaarhuis?) zitten twee tapeinden die duidelijk om "iets" vragen. Daar moet iets aan vastzitten. Weet alleen niet wat. Dat wordt dus zoeken. Verder ontdekte ik dat er spanning op de twee vorkpoten zat. Als je de wielas vastdraaid moet je aan de andere vorkpoot even de klem losdraaien. Weer zoiets dat de vorige eigenaar duidelijk niet wist. Even lossen en weer vastdraaien. | ||

|

||

| En na wat zoeken komt er altijd wel weer een oplossing. Er ontbreekt dus een montageplaat om het blok aan het frame te verbinden. Ook die gaan we weer zoeken. | ||

| 5-1-25: | ||

|

||

| Nieuwe lange zondag en nieuwe kansen. De motorbevestiging gemonteerd zonder speling dus met wat vulringen. Zit die ook weer vast. Verder waren de remspullen binnen gekomen. | ||

|

||

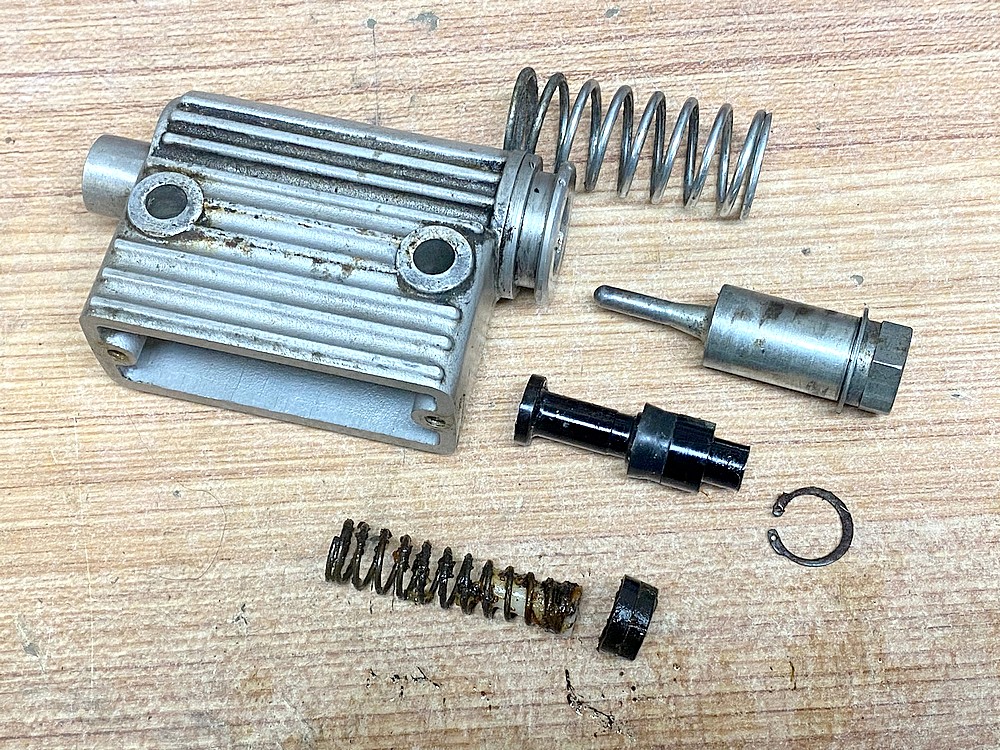

| Veel gedaan vandaag. De rempomp op het stuur vertrouwde ik niet dus die maar goed schoongemaakt. Was niet voor niks, alles zat vast. Netjes schoongemaakt en hij werkt weer. Was nog even een leermomentje om alles weer terug te zetten. Veertjes springen wel eens weg en je vind ze moeilijk terug. Natuurlijk vond ik nog de juiste remolie terwijl ik al voor veel geld een nieuwe pot had gekocht. Zo gaat dat. | ||

|

||

| Remklauw voorzien van nieuwe blokken en ontlucht op de ouderwetse manier en hij remt nu als een gek. Die vreselijke lelijke leidingen werken wel een stuk beter dan die oude rubberen dus laten we ze nog even zitten. | ||

|

||

| Alles bij elkaar en monteren was nog even puzzelen. Op Youtroep zag ik een video waar ze voor het gemak die veren maar weglieten. Lijkt mij een uitdaging om ze wel te gebruiken. Was even prutsen maar daar doen we het voor, het zit. | ||

|

||

| Ziet er weer netjes uit en hopelijk remt hij ook beter dan de meeste van zijn soortgenoten. Nog even wachten op een revisiesetje van de rempomp. Er werd een verkeerde gestuurd. Dan de remolie DOT 5 er in, ontluchten, en weer een klus geklaard. Uiteindelijk maar niet gewacht. Alles schoongemaakt en gemonteerd en het werk weer prima. | ||

| 7-1-25: | ||

|

||

| Ik weet niet waarom precies maar bij elke Sportster die ik heb gehad zit meestal een ander voorspatbord, liefst chroom. Die vind ik nu eenmaal passen bij de tijd en model vooral dit model dat wat boller is dan origineel. Ze zijn inmiddels wel wat moeilijker te vinden maar Ebay in Duitsland gaf weer de oplossing. Maakt het helemaal af. Wat zijn de volgende stappen? Carburateur en alle olie nakijken en dan de uitlaten er op en maar eens gaan kijken of daar klappen uit willen komen. Zit nog te denken aan een sissybar omdat ik die heb liggen. Ook het stuur moet er aan geloven want er zitten wat risers in de pijplijn. Iets hoger stuur kan wel. | ||

| 8-1-25: | ||

|

||

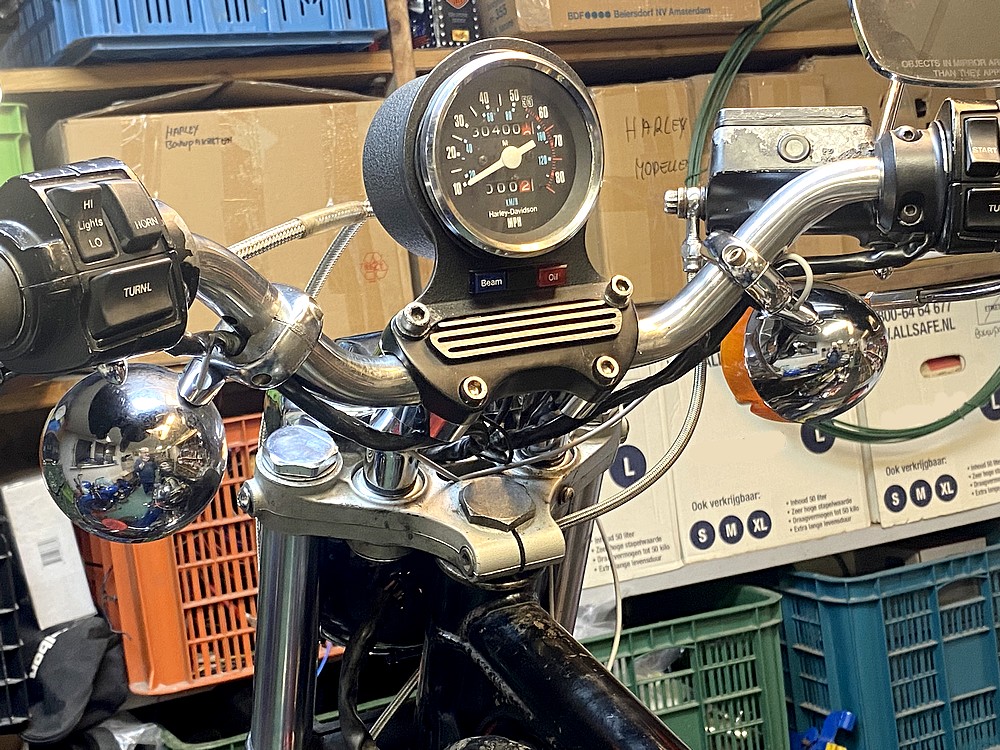

| Keuzestress, worden het de korte of worden het de lange risers. De korte komen uit China en de langere van Marktplaats. De motor zocht ze zelf uit en het werd bepaald door de lengte van de draadjes van de kilometerteller. | ||

|

||

| Zo ziet de huidige situatie er uit met de korte rechte risers. De knipperballen zaten eerst aan de spiegels gemonteerd maar had ik al er af gehaald. De teller zit hier tegen de "wenkbrauw" op. Zo heet die chromen kap boven op de koplamp. | ||

|

||

| Uiteindelijk werden het dus de korte risers waardoor het stuur iets hoger en wat meer naar achteren komt te zitten. Ik vond in mijn rommel nog twee belachelijke stuurklemmen waar de knipperballen op vast zitten. Met het lage stuur komen ze wat minder mooi uit maar ik vind ze prachtig. De teller zit niet helemaal zoals ik wil maar had even geen zin om alles weer te slopen om de montageplaat om te draaien. Komt wel. | ||

| 13-1-25: | ||

|

||

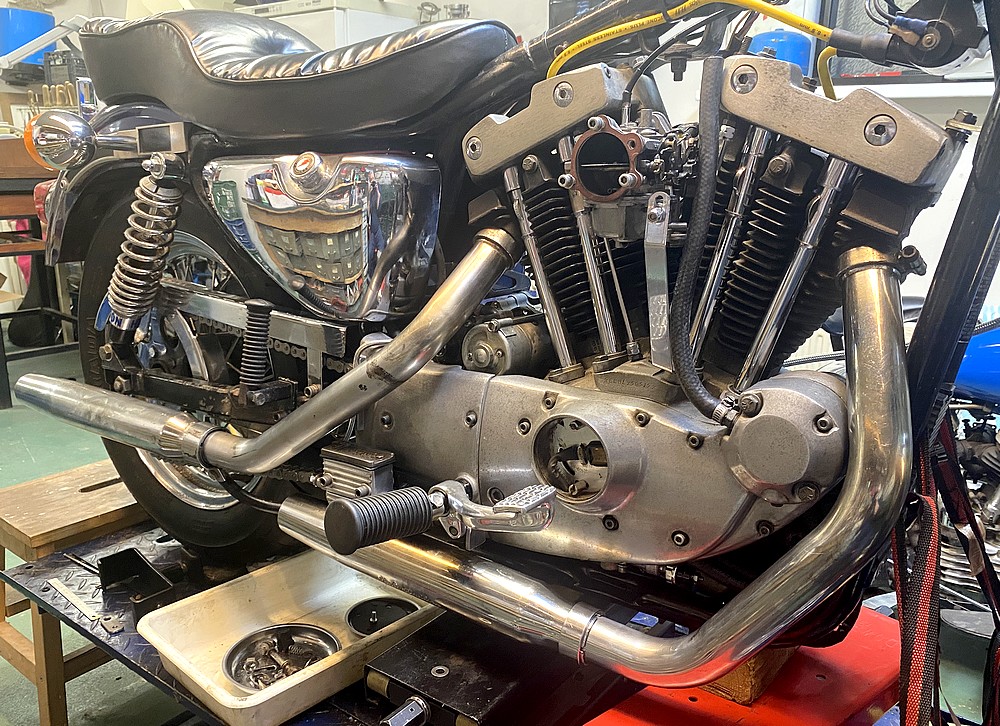

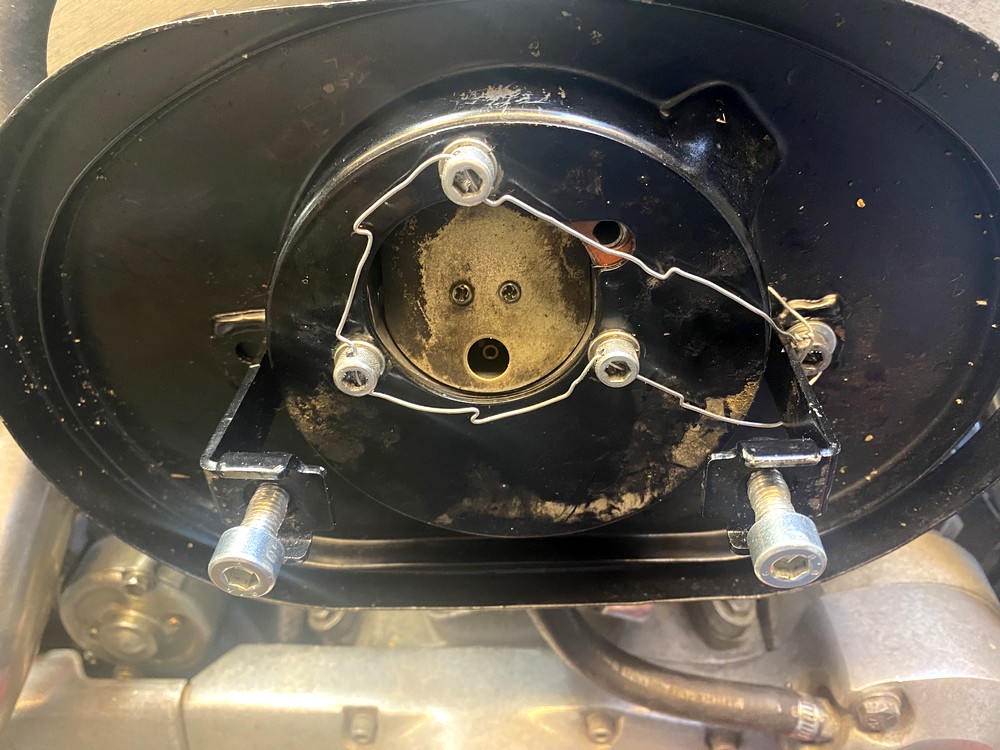

| Mooi blok toch hè? Na weken zoeken eindelijk dan een origineel luchtfilter gevonden op Ebay.de. Verkoper was wat stug maar uiteindelijk maar de goudprijs betaald want ik wilde hem hebben en in Nederland lukte dat niet. Er zijn wel meer onderdelen die net iets anders zijn dan die van voor 1983 of na 1986. Toen kwam de EVO en die was in detail toch heel anders hoewel veel onderdelen dan toch wel weer passend zijn te maken. De partsmanuals uit die tijd zijn ook heel verwarrend omdat ze vaak onderdelen uit verschillende jaren bevatten. In de manual van 83, 84 en 85 staan bijvoorbeeld ook onderdelen uit 79 tot 82. | ||

|

||

| Het luchtfilter maar meteen goed gemonteerd met een steunbeugel aan de achterkant om de carburateur te stabiliseren. Dit type blok wil nog wel eens wat vreugdetrillingen produceren. In die tijd begon men zich ook te interesseren in het milieu dus moest de ontluchtingslang aan het luchtfilter gemonteerd zijn. Ook gedaan. | ||

|

||

| Die knipperballen hebben nu wel zo'n beetje overal gezeten. Onder de spiegels, aan speciale mooie beugels maar nu op een plek waar je ze niet vaak ziet zitten. Het kan niet anders want op de andere plekken komen ze tegen de tank. En dat is niet prettig toch? Het komt door de risers die het stuur iets naar achteren brengt waardoor alles erg dichtbij de tank zit. Gelukkig had ik alles nog liggen. Het zijn originele onderdelen. Of het mooi is? Wie zal het zeggen. | ||

|

||

| Druk druk druk maar toch even de uitlaten gemonteerd zodat ik komende dagen kan gaan kijken of er wat geluid uit het blok komt. Het zijn originele pijpen met FXR dempers uit dezelfde periode. De achterdemper zit nog niet helemaal zoals ik wil. | ||

| 14-1-25: | ||

|

||

| Aan de linkerkant is er ook weer van alles aan de hand. Achter het driehoekige afdekkapje zit de bedrading en electronica. Achter de bak daarvoor de accu. En ook daar mijn lesje weer geleerd. Heb meer naar de prijs gekeken dan naar de maat van de accu. Resultaat is een goedkope gellaccu maar een hoop geknoei om alles passend te krijgen. De bovenste afdekkap maakt bijna kortsluiting omdat de polen ergens anders horen te zitten. Na het aanpassen van het kapje en veel rubber zit het hopelijk goed. | ||

| 15-1-25: | ||

|

||

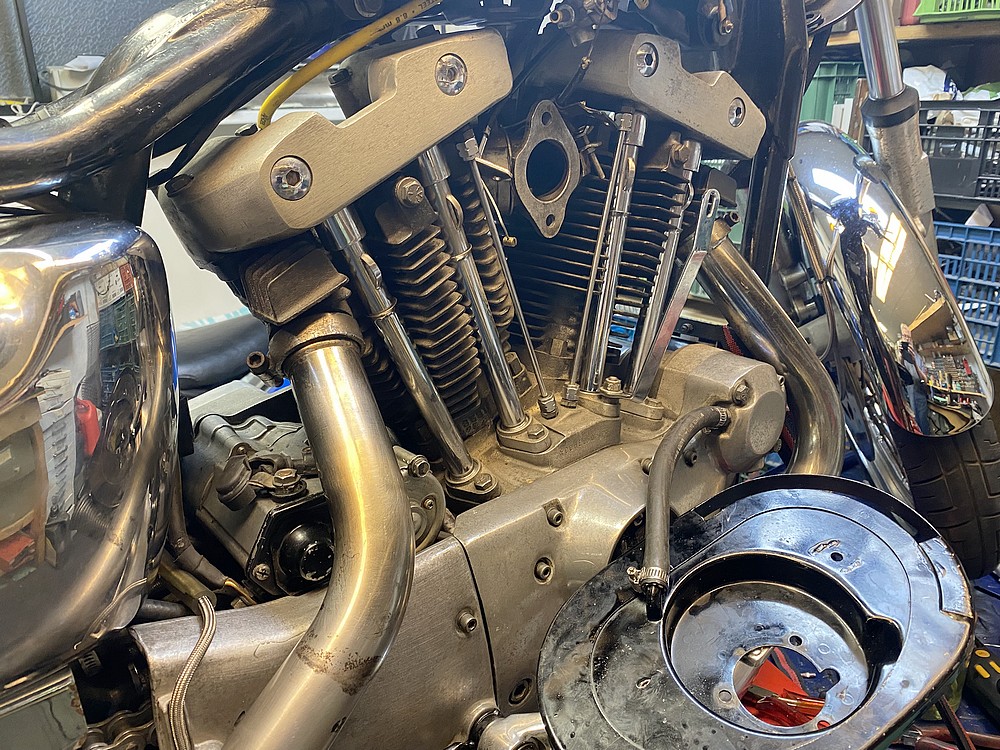

| Mooi blok hè. Al werkend herinner ik mij steeds meer trukjes hoe je met een Ironhead moet omgaan. Om de ontsteking af te stellen moet je een streepje vinden via een gat in het carter net onder de claxon. Op de krukas zit een streepje en een soort centerpunt. Als je dan met een afstellamp die ontsteking wil najkijken of afstellen moet je in een gat kijken waar een flinke straal olie uit schiet recht in je gezicht. Geen pretje. Maar er is een oplossing. Kijk maar hieronder. | ||

|

||

| Hier zie je het streepje dat aangeeft dat de voorste cilinder in zijn bovenste punt staat. Nee, ik heb geen blond krulhaar maar een nieuwe bril nodig zo te zien. Dat streepje is zeer moeilijk te zien als de motor draaid en de carterdruk door het gat naar buiten spuit. | ||

|

||

| We gaan er wat aan doen. Eerst met een wattenstaafje het streepje goed ontvetten en schoonmaken. Ik gebruik meestal wasbenzine. Dat verdampt snel. | ||

|

||

| Dan met een houten tandenstoker wat witte verf in de markering aanbrengen. Valt niet mee om er bij te komen maar zo is het wel goed. | ||

|

||

| Er is een perspex moer te koop om het gat dicht te schroeven om de carterdurk lekker binnen te houden. Op Ebay $39 maar op Ali gewoon 10 euro. | ||

|

||

| Iets verderop zit nog een ronde markering. Ben vergeten waarom precies maar denk dat het met de voorontsteking te maken. Zoek ik nog even op. Het streepje is belangrijk. Nog even de verf laten drogen en wachten op wat onderdelen maar dan wat benzine in de tank en kijken wat er gaat gebeuren. Heb de hele week al klusjes gedaan om dat moment vooruit te schuiven. | ||

| 16-1-25: | ||

|

||

| Gedenkwaardige dag. Motor gestart met wat remmenreiniger en hoppa, hij liep. Nu dus de benzine en carburateur gaan nakijken en maar eens opnieuw starten maar nu op de echte manier. Kwam er wel op tijd achter dat er helemaal geen olie in het blok en primair zit en die heb ik net niet in huis. Helaas geen foto of video gemaakt. Komt goed. Kreeg ook eindelijk de partsmanual binnen uit de VS. Nu kan ik tenminste de juiste partsnummers gebruiken. | ||

| 19-1-25: primaire kettingkast en een hoesje | ||

|

||

| Toen ik ontdekte dat de olietank helemaal leeg was begon ik mij zorgen te maken over de andere kant, de primaire kettingkast. Na controle van de spanning op de ketting zag ik al meteen dat daar erg veel speling op zat en geen olie te bekennen. De stelschroef om dat bij te stellen ontbrak. Geen idee wie er aan deze motor gewerkt heeft maar ik kan hem wel schieten inmiddels. Wat een knutselaar. Was nu bang dat de hele stelschoen niet aanwezig was in de primair en ik kon hem ook niet goed zien zitten. Zat niks anders op dan de deksel te verwijderen. | ||

|

||

| En voor dat ik het wist was het weer een puinhoop van rondslingerend gereedschap. Ik kreeg aanvankelijk de deksel er niet vanaf. Na een nachtje slapen maar eens rustig alles bekeken en zag toen dat ook de koppelingsafstelling los moet worden gedraaid. De afstelling voor de ketting zit er gelukkig in. Ik heb geen pakking maar ik ga hem weer in elkaar zetten met vloeibare pakking. Moet goed genoeg zijn. | ||

|

||

| Het hele zaakje zit weer in elkaar. De veer om de ketting te spannen zit nu goed en is weer bij te stellen. Dacht er nog even aan om de deksel te polijsten maar had er geen zin in. Ik heb hem maar met schuurpapier 600 en olie mooi mat geschuurd. Alles verder goed schoongemaakt en gecontroleerd. Deze keer gebruikte ik dus vloeibare pakking. Nog nooit gedaan maar iedereen is er tegenwoordig lovend over dus dat gaan we zien. Niet te zuinig mee geweest Even 24 uur laten drogen en dan kan de olie er in dus als hij gaat lekken dan heb ik het niet goed gedaan. | ||

|

||

| Nu alles los was kon ik meteen even uitproberen of mijn nieuw gevonden kabelhoes zou werken. Vind het een hele verbetering maar nog niet helemaal tevreden. Misschien was krimpkous toch beter geweest. Dit spul kan natuurlijk vuil aantrekken en is moeilijk om schoon te maken. | ||

|

||

| Volgende klus wordt de kleppen stellen. Ik vertrouw nu helemaal niets meer aan de motor. Is overigens een vrij simpele klus. | ||

| 20-1-25: | ||

|

||

| Tip van de dag: ga niet naar een harleyshop als ze aanbiedingen hebben. Kom je thuis met spul waarvan je denkt dat je het nodig hebt. Een platte buddyseat, korte sissybar en kussen voor de andere, Nieuwe hendels, een nieuw origineel buckhorn stuur nog in de verpakking, de pakking voor de primaire kettingkast die ik gisteren niet had en halve maar origineel achterlicht voor de WLC. Oja, versnellingsbakolie, die had ik wel nodig. | ||

|

||

| Zoals beloofd, kleppen stellen. Viel allemaal wel mee maar toch twee kleppen die te strak stonden. Is een klusje. De klepstoterhulzen zijn er zo af maar weer terug was even oefenen. Tegen de tijd dat je het weet zitten ze er alle vier op. De draadjes houden de hulzen omhoog en dan kun je de stoters zelf draaien. Als ze draaien is het goed maar ze mogen niet op en neer gaan of vast zitten. Klepstellen gaat dus helemaal op gevoel, dat is wat anders dan bij Japanse motoren. Niks met voelermaatjes of stelplaatjes. | ||

|

||

| Voor de zekerheid heb ik de boutjes waarmee het luchtfilter aan de carburateur zit even doorgeboord en geborgd met een draadje. Je moet er niet aan denken dat er een los loopt en naar binnen wordt gezogen. | ||

| 23-01-25: | ||

|

||

| Helemaal niet belangrijk maar vooral leuk om te doen. Zit nog even te wachten op wat bestelde onderdelen dus nu maar alle bij elkaar gescharrelde onderdelen aan elkaar gesleuteld en het ziet er allemaal weer gelikt uit. Een korte sissybar is moeilijk te vinden maar zo ziet het er netjes uit en kan de platte buddy er ook op. Eventueel met een klein kussentje. | ||

|

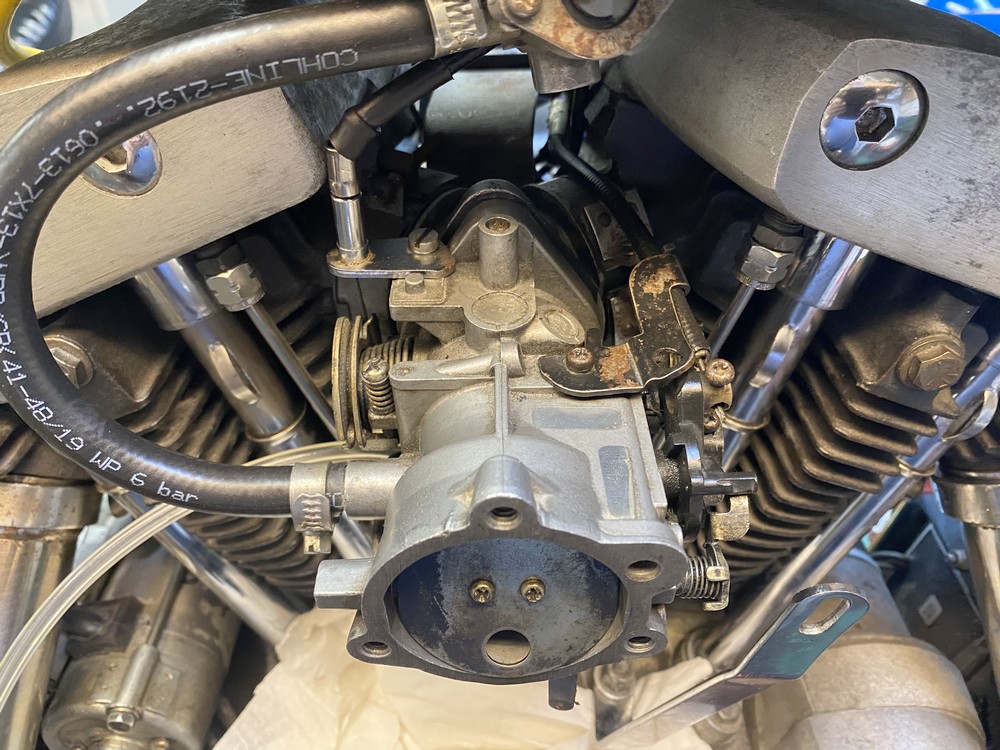

||

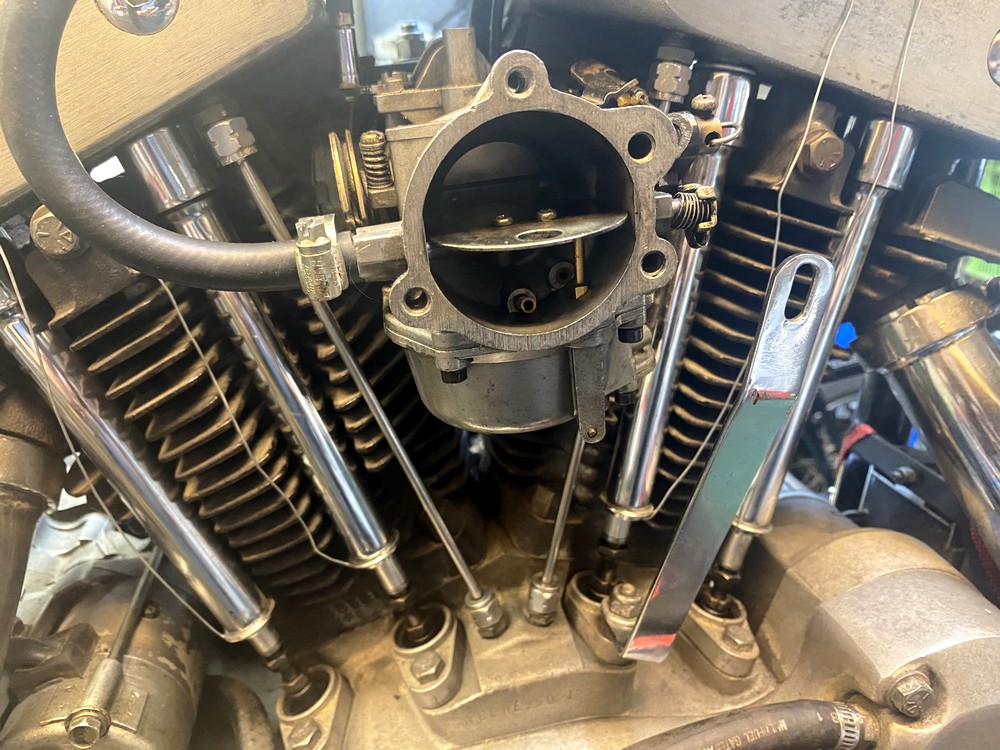

| Inmiddels is mijn vertrouwen dus helemaal weg dus vond ik het verstandig om de carburateur maar eens onder de loupe te nemen. Grotendeels uit elkaar gehad en alles zag er wel schoon genoeg uit om hem weer in elkaar te zetten. Aanvankelijk stroomde de overloop van de vlotterkamer over maar na het iets bijstellen van het veertje was dit ook weer in orde. | ||

|

||

| Het hele zaakje gemonteerd en nu is het wachten op een dag dat er geen mensen in mijn sleutelhok zijn die meestal niet van uitlaatgassen en benzinedampen houden. Zaterdag ga ik kijken of hij wat wil lopen maar dan wel buiten. Hij maakt al wat klappen maar ik heb de tank nog niet gevuld met benzine. Komt zaterdag wel. | ||

|

||

| Hele luchtfilter zit nu met inhoud stevig vast. Het enige dat ik mij nog kan bedenken is de afstelling van de ontsteking. Als hij loopt gaat hij even in de hoek om plaats te maken voor mijn andere project. In het voorjaar mag hij even naar de RDW. | ||

| 25-01-25: | ||

|

||

| Na bijna 3 maanden is dit project voorlopig weer klaar en ik ben tevreden. Had hem buiten gezet om hem te laten lopen. Binnen deed hij dat prima maar eenmaal buiten? Helemaal niets meer. Dus maar weer op de bok zetten. | ||

|

||

| Ben met de carburateur bezig geweest en misschien dat daar iets niet goed gegaan is. Eerst eens naar de vonkjes gekeken en die waren goed. Wordt dus een carburateur dingetje. Verder lekt hij uit de primaire kettingkast. Daar moet echt een pakking in. | ||

|

||

| Ondertussen wat platen geschoten voor het geval hij weer op marktplaats beland. Als hij blijft ga ik hem na de keuring wel wat pimpen. Wat precies weet ik nog niet maar in ieder geval een hoger stuur, andere buddy en een ander kleurtje. Of misschien blijft hij wel zo. Je vind ze niet snel meer, een originele uit 1984. | ||

| 26-01-25: lopen, niet lopen, lopen, niet lopen | ||

|

||

| Maar hij ging weer snel de bok op. De primaire kettingkast lekt zoveel olie dat het duidelijk is dat er echt wel een pakking in moet. Verder wilde hij niet lopen op benzine uit de carburateur maar wel op remmenreiniger. Duidelijk een carburateur probleempje. Dat was weer snel opgelost en zowaar hij wilde lopen. Nog niet lekker maar dat is ok. | ||

|

||

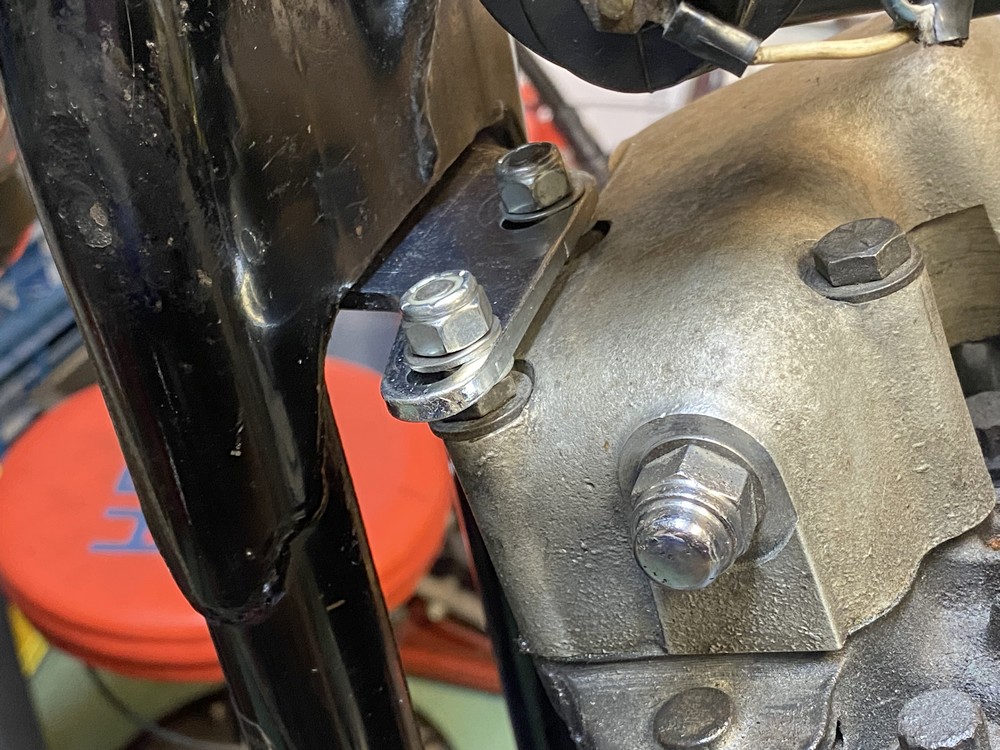

| Nu hij loopt werd duidelijk waar er olie uit kwam. Alle bouten op deze foto zaten los. Allemaal, gewoon niet aangedraaid. Stom van mij dat ik die nou net niet gecontroleerd heb. Dus de primaire kast was niet de schuldige, voorlopig. De olie kwam dus uit de andere kant toen hij eenmaal liep. Maar een oud gezegde luid: als er olie uitloopt zit er nog wat in. Morgen maar even kijken welke olie er nog onder ligt. | ||

| 28-01-25: een soort van klaar | ||

|

||

| HIJ LOOPT, eindelijk. Na vier keer de vlotter te hebben afgesteld, nieuwe bougies gemonteerd en een gebroken draadje gevonden te hebben. Tik maar op de foto voor een videootje. | ||

|

||

| Het kan nu best zo zijn dat er hier een voorlopig einde is gekomen aan dit project. Hij gaat even onder een dekentje tot ik weet wat ik er mee ga doen en schuif naadloos door naar mijn volgende project, een WLC. | ||

| 1-5-25: wat lekkage | ||

|

||

| Toen ik een paar weken geleden eens even naar hem omkeek en zijn dekentje eraf trok had hij een wat olie gelekt. Geen idee waar vandaan. Eerst dacht ik uit de primaire kettingkast maar na het flink aandraaien van de bouten was dat weg. Maar er lag een plas zwarte olie onder. Terwijl er toch vrijwel kleurloze nieuwe olie in is gegaan. Misschien is het de oude olie uit het blok. Natuurlijk was de accu leeg dus morgen maar eens even starten en kijken of de olie wel terug naar de olietank komt. Dat bleek zo te zijn. Het enige dat ik mij kan bedenken zijn de olieslangen vanaf de oliepomp. Maar dat gaan we pas zien als de accu en accubak er eerst "even" vanaf gaan. | ||

| laatste | ||

|

||

| Veel van de verhalen op mijn site beginnen met een foto van een bestelwagen met een motor daarin. Soms komen ze er een brengen en soms gaat er een weg. In dit geval gaat de prachtige Sporter naar een nieuwe eigenaar. Of ik hem ga missen? Waarschijnlijk wel. Ongetwijfeld zal er weer wat anders langskomen. Nog ff wat geschiedenis: | ||

|

||

|

HARLEY-DAVIDSON XLX CYCLE WORLD TEST A human touch for a high-tech world Here’s the Harley-Davidson XLX, the no-frills Sportster. It seats one. It doesn't have a radiator, a shaft drive, banks of solid-state instruments. There are no multi-anythings; not valves, nor pistons. This test contains not one line about New! New! New! or Fastest! or Quickest! or Never Before!. And we love it. The XLX hasn’t been parked since it arrived. The tourers, the racers, the dirt guys, L the technical freaks, are all arguing over whose turn it is to ride the Harley this weekend. The XLX is an elemental motorcycle, stark in its simplicity. It has two wheels, two disc brakes, forks, dual shocks, two air-cooled cylinders, a single carb and air > cleaner, two chrome exhaust pipes, a gas tank, an oil tank, a seat, a speedometer, basic lights, a battery, all out in the open and easy to spot and identify and understand. The engine is Harley-Davidson’s unitconstruction Sportster motor, a longstroke (bore and stroke are 81 x 96.8mm), lOOOcc, ohv, 45° Vee. The cylinder head and cylinder are cast iron, just like the 1952 750cc sidevalve engine from which the current powerplant evolved. There are two valves per cylinder set in hemispherical combustion chambers, the valves open via rocker arms and pushrods operated by a set of four single-lobe cams arranged in the vertically-split crankcases, to the right and just below the cylinders. There’s a single 34mm Keihin carburetor (with an accelerator pump and an oiled-foam air cleaner) feeding both cylinders from the right side of the vee, through a Y-shaped manifold. The front cylinder’s exhaust exits forward, and the rear cylinder’s exhaust flows rearward; each cylinder has its own short, chromed exhaust pipe and muffler, with a balance tube linking the head pipes. This is a dry-sump engine, with an oil tank bolted to the right side of the frame, under the seat. There’s a separate oil supply in the primary case for the duplex-roller chain linking the crankshaft and the multi-plate wet clutch, and for the four-speed transmission. Final drive is a 530 roller chain without O-ring seals. Both one-piece connecting rods ride on the roller-bearing crankshaft’s single throw. The rods aren’t side-by-side. Instead, the big end of one rod is forked, and the narrow big end of the other fits between the fork. The three-ring cast aluminum pistons have high-peaked domes, but compression ratio is a mild 8.8:1, thanks to the tall combustion chambers. Steel struts are cast into each piston between the skirt and the wrist pin boss to help match piston and cylinder expansion rates. Ignition is electronic with two advance curves built into a micro-chip control. A vacuum switch positioned on the carb bracket selects which curve is followed at any given moment: high vacuum, low load triggers the upper curve with more advance, sooner; low vacuum, high load has the ignition follow the lower curve with less advance, later. Advance is 8° at startup and advances according to rpm and load. Maximum advance is 40° BTDC. Despite all those familiar features and specs, despite the heritage reaching back to the side-valve Model K motors, it would be a mistake to think this Sportster engine is the same as those before. It isn’t. The factory has continued with evolutionary improvements, improvements that become obvious when the 1984 XLX is compared with even the most recently previous Sportsters. Take the clutch. It’s all-new (sorry, that just slipped out), with an aluminum alloy basket, aluminum-base friction plates, and a single diaphragm spring instead of six coil springs. The change to a diaphragm spring makes a dramatic difference, because it takes the amount of effort needed at the lever out of the bodybuilding catagory into the 20th century. And because the diaphragm spring has an over-center effect as the clutch is disengaged, the amount of force needed to pull the handlebar lever drops from an initial 18 lb. to just 6 lb. at the grip. More oil flows through the new clutch, helping to carry away heat, and the entire assembly is significantly narrower than the old clutch. That narrowness allowed Harley engineers to add a 240-watt alternator on the clutch shaft, behind the clutch itself. The alternator replaces the 156 watt generator formerly mounted at the front of the crankcases and driven off the crankshaft by a set of three gears. A spin-on oil filter takes the place of the generator on the crankcases, with minor changes in the oiling system to accommodate this. The transmission output shaft has a new needle roller bearing instead of loose rollers and the output shaft oil seal is pressed into the crankcases instead of being held in place by a bolt-on cover. The result is that the 1984 engine is 13 lb. lighter than the 1983 engine, puts out more electrical power, has a lighter clutch pull and is mechanically quieter (thanks to the elimination of the three generator drive gears). Rake and trail are 29.7°and 4.5 in., wheelbase 59.5 in. The XLX frame is made of round steel tubing; the backbone is formed by a single large tube running from the steering head, over the engine, and then curving down behind the engine to the swing arm pivot. Two smaller tubes run down from the steering head to form an engine cradle. Two other tubes branch back from the backbone to support the dual shocks and seat, and loop forward to meet the engine cradle tubes. The swing arm is rectangular steel tube and straddles the backbone; the swing arm pivot axle fits through the backbone tube and rides in two tapered roller bearings on the right (drive) side and in a single bushing on the left side. The rear axle is carried by sliding blocks fitting inside each end of the swing arm; chain tension is adjusted by turning a self-locking nut on a stud protruding from each block. The engine is rigidly mounted front and rear, and a steel strut bolts between the cylinder heads and the frame and doubles as a mount for the ignition switch, choke knob and horn. The 3.0-qt. oil tank fastens to the right side of the frame, the battery box to the left. Both front and rear fenders are rolled steel. There’s a solo seat with a plastic base and vinyl cover and a 2.25gal. steel gas tank with a screw-in cap. The left footpeg bolts to the primary cover; the right peg to the engine sprocket cover. The handlebars are conventional steel tubing. The forks have 35mm stanchion tubes and are non adjustable. The steering stem pivots in tapered roller bearings. There’s a single 11.5-in. stainless steel disc on each cast aluminum alloy wheel, a 2.15 x 19-in. front and a 3.00 x 16-in. rear. Tires are Dunlop K181 s. The 5-inch headlight, rubber-mounted from a streamlined aluminum piece jutting forward from the upper triple clamp, looks small but packs more lighting power than its 35/50w low/high rating would seem to indicate—it is quartz halogen. There’s just one instrument, an accurate (60 mph indicated is an actual 59 mph) 85-mph speedometer with odometer and tripmeter, and warning lights for high-beam and low-oilpressure. There are turn signals, two clamp-on lights attached to the handlebars and two stalked signals mounted on the rear fender support brackets. The signals are activated by pushing blade-shaped buttons on the handlebar control pods. Each set of signals—right and left—has its own button, and flash only as long as the button is held down. There’s no indicator light to show that the signals are working, but the rider can see the signal lenses. There’s one rearview mirror, on the left side, with flat glass. Add up all the details and the XLX weighs 475 lb. on our certified scale, with half a tank of gas. That’s very light for a lOOOcc motorcycle. Sit on the XLX and it feels smaller than it is, partly because of that light weight and partly because the weight is carried relatively low, compared to a big-bore inline Four. The seat height is low, just 30.1 inches, adding to the small feel of the bike. Reducing weight is one way to increase performance, but the Sportster is not a dragstrip missile. The XLX thundered down the quarter-mile with a best pass of 13.88 sec. and 93.75 mph, the: clutch slipped to keep the engine from bogging in the tall first gear and the engine powershifted at the maximum calculated speed in gears at redline (6200 rpm) since there isn’t a tach. It was on the second of five passes that we powershifted the Harley, yielding that 13.88 at 93.75. The clutch was never the same again. The XLX became reluctant to shift from first to second no matter what the technique, and our quarter-mile testing ended. In the flying half-mile, the Harley reached 108 mph. It was different when it came time to test brakes. The combination of good brakes and tires and light weight allowed the Harley to record a spectacular 60-0 stopping distance of 112 feet. Control was excellent, although quick stops demand a hard pull at the lever; the clutch may be reformed but the brake still favors iron-pumping he-men at the controls. Stopping distance from 30 mph was also excellent, although not recordsetting, at 32 feet. The brakes also work in the wet, as a sudden rainstorm showed us. The fenders fend better than most, too, doing an excellent job of keeping water thrown up by the tires off the rider and bike. The Harley’s fenders were built for more than looks. Trouble is, the dragstrip numbers don’t convey the feel, the character of this motorcycle. That can be a difficult concept to explain to riders used to the fastest, the quickest; riders prone to enjoy covering the distance from Point A to Point B in less time than a police helicopter. Difficult until those riders are sent out on the Harley to cover more than a few miles, farther than the corner all-night market. The irregular beat of the 45° Vee breathing through short, dual mufflers gives the XLX a rumbling, growling—yet legal—exhaust note, leaving behind a subdued thunder. Accompanying that thunder is vibration, the real, honest throbs of large pistons shot down cylinder bores by the violent explosion of compressed gasoline vapors. The Harley has big pistons and turns slowly—60 mph in fourth gear takes just 3200 rpm—and that means the power pulses are big and distinct. The vibration is not the buzz and thrash of a vertical Twin; there’s a cadence to it that makes it seem normal and natural and very mechanical. It is the feeling of a machine at work, and if it lacks the silky smoothness of a refrigerator or a Buick, so be it. The solo saddle is well padded. Some riders found it comfortable; others wished for a longer, wider seat with less of a rear hump. The pegs are a bit high and forward; the bars also high and forward. The suspension is middle-of-theroad, as compliant and quick to react as any other non-adjustable, simple forks and shocks, but not as good (and not as complex and not as heavy) as the multiadjustable, wide-range, state-of-the-art suspension seen on some bikes. First gear is taller than most, like second on a multi, and the gap between third and fourth is gigantic. The Harley handles both with torque, amazing quantities of an urge to move forward. Fourth is too low for fast cruising—four gears really aren’t enough—and the engine wants to pull another cog, a taller gear, a true overdrive perhaps. It’s smoothest at 55 mph, a motorcycle that runs best at the legal limit, and the vibration grows as the speed increases; at 65 mph cars in the single mirror are gross images and blurred colors, not distinct vehicles. The Sportster will run down the road at 85, 90, 100 mph; but the price paid for such speed is increasing vibration. The price paid is not unreliability. The Harley-Davidson XLX is reliable. The problems encountered with the Harleys of years ago are gone, much as new quality control efforts have improved American cars. The XLX was given no special treatment, and it didn’t break. It did use oil, two quarts in the first 1000 miles, perhaps because the rings need time to bed in. And it seeped a little oil, leaving a spot or two wherever the XLX was parked for long. The droplets came from the primary case, through the gasket and around the drain plug, and' blew back on the swing arm, rear wheel and rear disc. The XLX didn’t use much gas, typically travelling 95 hard miles before requiring reserve, taking 1.8 or 1.9 gal. when the tank was filled five or 10 miles later. That’s about 58 mpg. On the Cycle World mileage test loop—a 100-mile circuit of city, open country and highway riding—at legal speeds, the XLX delivered 60 mpg. This Harley-Davidson, this XLX, can be a surprising motorcycle. It is lots of fun in the city, booming through town and catching eyes with its metallic red (or black) paint and rakish profile. But it’s also stable and quick through the corners of a twisty road, speed past the apex limited only by dragging footpegs on both sides. The pegs drag too soon, but not so soon that a competent pilot on the XLX cannot startle a less-aggressive rider on a big Japanese sport bike. The Harley handles. And it is fun. Fun to ride. The guys who ride Harleys understand that a motorcycle can be fun, can give a rider what he wants, without having the most possible horsepower. That’s the Harley. Its appeal is different from the appeal of the fastest, the quickest; its appeal is in how it looks and feels and what it is. The XLX is an escape of sorts, perhaps even a protest, a vehicle out of the complexities and pressures and cares of the modern world. It is a motorcycle, plain and simple, honest and straightforward. |

||

|

This site is designed and made by Ben van Helden copyright on all pages |